Part 4 Prelude

Moral Decision Theory

In Comparison

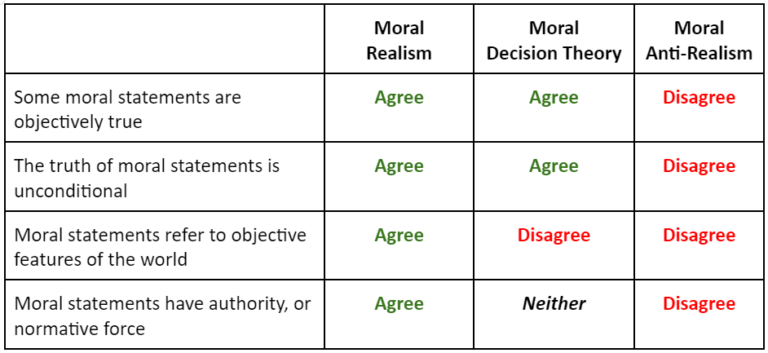

The study of the nature and meaning of moral propositions is known as meta-ethics. Within this field are two opposing positions, moral realism and moral anti-realism. Although there are other ways to categorise differing views, these are the terms primarily used to differentiate between meta-ethical viewpoints.

These two perspectives disagree on the meaning of moral statements, and on whether or not they can be objectively true. As shown in the table below, Moral Decision Theory takes a view which fits in between the opposing positions.

Where MDT agrees with the moral realist position is that both advocate that moral statements can be objectively true. According to MDT, the statement “A person should not violently attack a stranger when passing them on the street” is a fact. Based on the information available to that person, it would be incorrect to decide to violently attack a stranger. A moral anti-realist will deny that this statement is an objective fact, and so will be in opposition to MDT.

A moral realist will further claim that moral facts are true because of objective features of the world. This may involve the belief that actions or intentions have certain moral properties, or may be a belief in the existence of moral principles. Moral Decision Theory rejects these propositions, arguing instead that such positions have no justification. The moral realist will further understand morality to have an authority or normative force which is binding upon us. Moral Decision Theory makes no reference to any authority, focusing only on the truth of prescriptive propositions.

Part 4

Moral Decision Theory

In Defense

In Parts 1-3 I have tried to give a full explanation of Moral Decision Theory in terms of what we should decide and how we should decide. If you have read through these sections, you will hopefully have a clear understanding of the key ideas involved and of the way in which I have argued for its truth. However, you may still have some reservations or disagreements. In Part 4 I have tried to anticipate some objections and challenges to MDT, and have prepared a response accordingly.

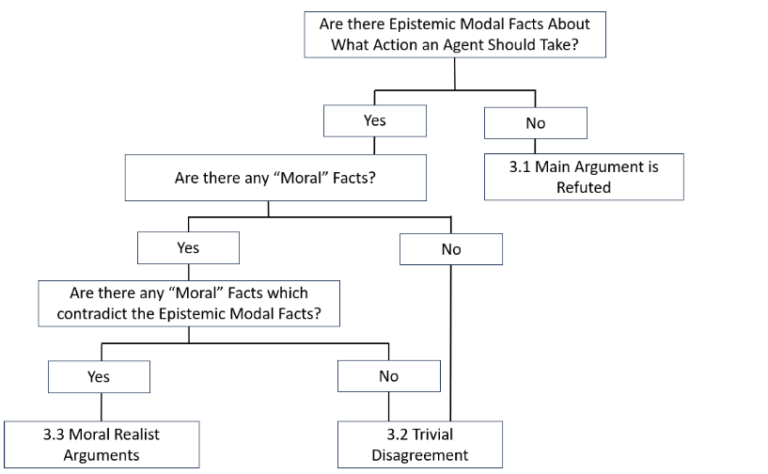

The objections to Moral Decision Theory can be separated into three main categories, as shown in the diagram below.

The first group are those which reject the central argument that there are unconditional prescriptive epistemic modal facts. These objections will refute at least some element of the argument made in Part 2. I have tried to anticipate some such objections, and provide a response in section 4.1 below.

Alternatively, there are some who may accept the argument in Part 2, but still deny Moral Decision Theory. The most basic objections include those who deny that Unconditional Prescriptive Epistemic Modal Facts can be labelled as Moral Facts. They may believe that moral facts require an additional supervening property, which disqualifies the prescriptive facts advocated by MDT. These objections are ultimately trivial, but are discussed further in section 4.2.

Others may believe that while I have accounted for the objectivity of Unconditional Prescriptive Facts, that these are separate from Moral Facts. These objections come from a position of Moral Realism, and will argue that another moral duty or moral principle is in conflict with the Unconditional Prescriptive Epistemic Modal Facts. I respond to these potential arguments in section 4.3.

There is a final group of objections which argue on more general terms. These are discussed in section 4.4.

4.1 A Direct Challenge

In Part 2, I have presented a structured argument for the objectivity of Unconditional Prescriptive Epistemic Modal Facts which are a logical consequence of the information available to an agent. Someone who disagrees with Moral Decision Theory may find that the argument made in Part 2 is either not valid or not sound, such that there are no epistemic modal facts about which course of action an agent should take.

4.1.1 Challenges to the Notion of Information

The foundation of Moral Decision Theory is the information available to decision makers. This refers to the information in the form of perception, or sense data, and memories. It would be quite unexpected for someone to object entirely to the notion of information and argue that agents do not have at least some information.

One might argue that information is not a real thing, such that it does not exist. Such an argument would not apply to Moral Decision Theory, which makes no claims regarding the ontology or existence of moral facts.

Another opponent may argue that we cannot draw conclusions on the basis of information which is vague or ineffable. When you look out your window and perceive the world, we might say that you receive or process sense data. This data, or information, cannot be described or communicated with perfect accuracy using language. If this is the case, no statements or propositions can refer to such information.

According to MDT, there are prescriptive facts about moral decisions which are founded on the basis of such vague and ineffable information. One may argue that prescriptive propositions cannot be the logical consequence of information, if that information itself, cannot be expressed accurately and completely in a proposition.

An opponent of MDT who makes this argument would have to reach the same conclusion about descriptive statements. For example, the proposition “Scotty can see a cow in the field” is a proposition based upon vague and ineffable sense data. As long as some accurate descriptive propositions can be made on the basis of information (perception and memory) then we can move forward with the argument towards prescriptive statements.

4.1.2 Objective Probability Seems Unlikely

Some have argued that only a subjective interpretation of probability exists. Their view is that probability reflects credence, or degree of belief (described in section 1.9.3) and has no basis in fact.

According to this view, someone may hold a belief that a coin has a 90% chance of landing on heads. This belief may accurately reflect their subjective feeling and cannot be considered wrong because there is no fact of the matter.

While some may hold this view, it is unlikely that they actually live by it. Suppose your friend told you of their belief that their favourite sports team had a 99.9% chance to win their next match. In accordance with this belief, they plan to bet their entire life savings upon that outcome. If you believe that probability is subjective, then you can make no argument to change this friend’s mind. Any information you give, and evidence, any reason or warning is irrelevant according to your view that probability is subjective.

Of course, some particular information might change your friend’s mind. For example, you could tell them cautionary tales of others who made similar decisions and lost. But changing your mind on the basis of information or evidence is consistent with the view that probability is logical or objective.

As explained in section 1.9.2, the interpretation of probability referred to by MDT is simply as a representation of incomplete information. Suppose I tell you that on Planet X, there are two sports teams, the Predators and the Xenomorphs. In the sport they play, there are no ties, such that one team must win. On the basis of this information, there is a 50% chance that the Predators will win. This has nothing to do with credence or belief. It is simply a logical consequence of the small amount of information provided. If further information was provided, then the uncertainty would decrease, and the odds would change.

4.1.3 The Nature of Experience

The next objection to the argument which someone may have relates to the nature of mental events, referred to as experience. Within the philosophy of the mind, there are many debates about the nature of conscious experience. Many philosophers take the view that experiences exist as something called “Qualia”. These are described as real things, or as constituent features of reality.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/qualia/

Some qualia, such as the experience of perception, have no valence in that they are neither positive or negative. However, others including bodily sensations, emotions and moods can have a valence and intensity. A worldview which includes reference to qualia will be consistent with the claims made by MDT.

However other philosophers, such as Daniel Dennet and Keith Frankish, have argued that qualia do not exist – that conscious experience is an illusion. However, even this view is consistent with MDT.

Illusionists do not deny the occurrence of experience, only the position that experience exists within a mental realm, separate from physical activity in the brain. To quote Dennet “Everything real has properties, and since I don’t deny the reality of conscious experience, I grant that conscious experience has properties.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zPKKGPRGRFs

A similar distinction can be drawn between dualism and physicalism. A useful analogy can be found by considering the concept of heat. Heat can be explained as thermal energy transferred between systems. It can also be explained as the motions and interactions of electrons, atoms and molecules.

Under one view, these two descriptions of heat represent entirely separate entities. Under another view, the heat is simply a higher level occurance of the same phenomenon. The first position is analogous to a dualistic view of conscious experience, placing qualia as independent from the brain. The second position is analogous to the alternative view which views experience as a higher level explanation of a physical event which occurs in the brain.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1KemhfmAsg8&t=2698s

Both of these perspectives on the mind, or on experience, are compatible with Moral Decision Theory. Factual claims can be made about experience whether it is believed to exist within a mental realm or as an aspect of physical events.

4.1.4 Objective Ranking of Experience

A common argument made by Moral Anti-Realists, especially against a utilitarian or hedonistic view of Moral Realism is that different consequences or experiences cannot be objectively compared to one another.

This particular argument does not actually apply to Moral Decision Theory as it refers to the concept of objective value. The comparisons made under MDT are those which rely on valence, not value. They are made upon the potential experiences which are simply the logical consequence of information available to the agent.

Moral Decision Theory makes no claims about the value of actual experiences. It makes no claims about whether an actual event or state of affairs is good relative to what may have occurred in a metaphysical sense. Instead, all comparative claims refer only to the epistemic notions of experience held by the agent.

4.1.5 The Is-Ought Gap

Another classic argument made by Moral Anti-Realists is known as the Is-Ought Problem, or Hume’s Law. This challenge, initially from David Hume, argues that one can’t move from descriptive statements (about what is) to prescriptive statements (about what ought to be). In parallel to this argument, someone may claim that one can’t move from Premise 14 about which action would be best to Premise 15 about which action should be taken.

The ‘ought’ being referred to by this argument is one which makes reference to an authoritative power or normative force. For example, someone may claim that humans have evolved to live together in groups, therefore, humans ought to cooperate with one another. Here, the conclusion that we ought to cooperate is considered to be binding upon humans because of our evolutionary background.

The is-ought problem may be insurmountable in reference to authoritative oughts, but has no relevance to cases where no such authority is presumed. Suppose you are walking with a friend when they turn to you saying “You should tie your shoelaces.” Your friend is not asserting that you have a duty or binding obligation to tie your shoelaces. They are simply recommending a course of action which they expect to be preferable.

As explained in section 1.4, Moral Decision Theory makes no reference to any authoritative force or binding obligation. The term “should” simply refers to a prescription that one course of action will have better outcomes than any other option available. For this reason, the Is-Ought Gap is not a problem for Moral Decision Theory.

4.2 Trivial Disagreement

The next category of disagreement comes from those who accept the claim that Unconditional Prescriptive Epistemic Modal Propositions can be objectively true.

4.2.1 The Moral Domain

As discussed back in Section 1.1, the term moral is used by different people and different cultures in different ways. Someone may argue that there are Unconditional Prescriptive Epistemic Modal Facts, but that despite this, there are no “Moral Facts”.

This opponent of MDT may argue that the term “moral” is not applicable to these epistemic modal facts. This is ultimately just a question of semantics, but is worth clarification.

Morality is generally considered to involve

- Impartiality: Moral judgements involve consideration of others without any selfish bias.

- Universality: Morality is applicable to all rational agents.

- Reactive attitudes: We have strong feelings towards moral judgements or prescriptions.

The first two of these are covered adequately by MDT. All Unconditional Prescriptive Epistemic Modal Facts involve impartiality and are applicable to the decisions of all rational agents.

The final element only applies to some subset of Prescriptive Facts. There will be some such facts (e.g. You should brush your teeth) which may be objectively true, but which few of us have strong attitudes towards. There will be other such facts (e.g. You should not torture babies) which almost everyone will feel strongly about. The distinction between the two, the decision to place a sentence in the former group or the latter will be subjective. This shouldn’t come as a surprise given this final element refers to subjective attitude. However, as long as some Unconditional Prescriptive Epistemic Modal Facts refer to “moral” decisions, we can classify them as Moral Facts.

Different people will have different views of the classification, or different reasons for classification. But if we agree that some facts fit our definitions, then some facts are moral.

4.2.2 Supervenience of Values or Duties

Another opponent will hold the following views

- There are objectively true Unconditional Prescriptive Epistemic Modal Facts

- Some prescriptive facts are Moral Facts because of some additional factor which is not accounted for by Moral Decision Theory.

This person would believe that moral values or moral obligations supervene upon the underlying facts of the agent’s decision. Any changes to those underlying facts would result in a change to the supervening moral properties.

This view, is in a sense, complementary to Moral Decision Theory, rather than in contradiction to it. As long as there is a 100% overlap between the Unconditional Prescriptive Epistemic Modal Facts and the Moral Facts which supervene upon them, then no further discussion is required.

4.3 Morality & Ontology

The next group of objections will come from someone who accepts the argument as detailed in Part 2, but who believes the conclusion to be in opposition to some other perspective on morality. This opponent will hold the following views

- There are objectively true Unconditional Prescriptive Epistemic Modal Facts

- Some Unconditional Prescriptive Epistemic Modal Facts are in disagreement with some Moral Facts

A person who holds this view will be an adherent to at least some version of Moral Realism. They will argue that their moral principles or moral duties are in conflict with the conclusions of Moral Decision Theory.

4.3.1 Actual Consequences

Someone may believe that in certain situations, based on the information available to an agent they should take Action A, but that taking Action B is “objectively better” because of the actual consequences which occur.

Phillipa is sitting on a bus when an old and frail lady gets on. She kindly stands up, giving up her seat for the old lady. A few minutes later, the bus swerves to avoid an accident. Unfortunately, a heavy suitcase falls onto the old lady, breaking her collar bone. Had Phillipa been sitting there, she would have been able to catch the bag. In this case, the actual negative experiences of the old lady are worse than would have been the case, had Phillipa not given up her seat.

If someone makes the claim that morality is contingent on actual consequences then it ceases to be action-guiding. When the correct thing to do is unconnected with the information available to an agent, we can only use morality retrospectively. In advance of a lottery draw, it is completely useless to say “You should pick the winning numbers”.

When talking of actual consequences, there may be true propositions about which actual experiences have a positive or negative valence. However, this is not a proposition about the decision made by the agent. It is ultimately no different to making claims about an earthquake being bad, or a sunny day being good.

4.3.2 Objective Value

According to Moral Decision Theory, the best set of subsequent events are those experiences which are most positive according to the information available to the agent. Best simply means most good (or last bad), where good is a property of certain mental events. However, someone may believe that a different set of subsequent events are best, according to some other criteria, that is to say that certain events have an objective value. This objective value, such a position would claim, should influence the agent’s decision beyond consideration of subjective experience.

Suppose that Ralph believes that honour is objectively valuable, such that people should act to increase or maintain their honour. Ralph is with his wife Lisa when a stranger makes an offensive remark towards her. Ralph believes that by physically attacking the stranger, he will have defended his own, and Lisa’s honour. However, according to Moral Decision Theory, the best course of action would be to de-escalate the situation, to stand-up to the stranger, but to avoid violence. He should also involve Lisa in the decision to respond, rather than act on her behalf.

There is a conflict between the unconditional prescriptive epistemic modal fact and the concept of objective value. To reach a resolution, we must investigate the notion of objective value.

To say that the consequences of our actions, or a particular state of affairs, are objectively “good” or “valuable” means that there must be an objective standard against which it is measured. To be objective, this standard must be stance independent – i.e. not created or formed on the basis of a subjective perspective.

But, you can’t have value, without a valuer.

The universe doesn’t have a perspective, but even if it did, that would still be a subjective one. You might argue that society or humanity has an interest in the objective good. But again, the perspective of a group is a subjective one. Different societies or groups would have different perspectives.

The proponent of objective value may respond that certain things (events, intentions, actions, or circumstances) are simply intrinsically valuable.

The first response is to highlight that this value is superfluous and therefore irrelevant. When making decisions according to MDT, an agent must consider how their actions may affect any and all individuals involved. Each subsequent event is compared in reference to how it matters in the eyes of each individual.

The claim that objective value supervenes upon these subjective experiences, means that it goes beyond what has already been accounted for. We can conclude that the “additional“ value which is objective doesn’t actually matter to anyone who is affected by the decision.

The honour which Ralph seeks to maintain is of no consequence to anyone in the situation. He may have positive feelings of pride and respect if he maintains his honour, but these have already been accounted for under MDT. Any additional value has no impact on the positive or negative experiences of anyone, because such impacts refer to the already considered subjective experience. Objective value is, by definition, of no value to anyone.

We could imagine objective value as existing on some kind of cosmic scoreboard upon which our actions are recorded. But if this is independent of any individual’s thoughts or feelings, then the points don’t matter.

It is therefore completely arbitrary to consider objective values when making moral decisions. Where Action A is best for the individuals involved, but Action B is best according to certain objective values, then choosing Action B would actually be worse for those affected.

A second argument against the existence of objective value comes from Mackie, and is known as the “Argument from queerness”. I won’t repeat the argument which is adequately explained elsewhere. In summary, we can simply place the burden of proof on those which claim that objective values exist.

4.4 Moral Duty

Within MDT there is no (objective) categorical distinction between a decision concerning which knife is appropriate for chopping vegetables, and a decision concerning whether it’s appropriate to attack a stranger with that knife. Many of us may feel that the statement “You should not stab that innocent person” carries some authority or normative force, while the statement “You should not use a butter knife” does not. This authority gives rise to a sense of moral duty or obligation which is not addressed by Moral Decision Theory.

Someone may believe that in certain situations, they have a moral obligation to act in a certain way. Such an opponent to MDT may recognise that there could be an Unconditional Prescriptive Epistemic Modal Fact that they should take Action A, but that there exists a moral obligation to take Action B.

To give a more concrete example, we might suppose that Javier believes that he has a moral duty to tell the truth. His friend Eleanor has cooked a meal which Javier found unpleasant. She presses him for feedback, such that he cannot avoid sharing a response. Let’s assume that under MDT, the best option is to compliment the meal – a lie. However, Javier believes that he should ignore this, and tell the truth.

To respond to this argument we must recognise that “moral obligation” can mean a variety of different things. Different people will account for the occurrence of such an obligation, or for the nature of the authority involved, in different ways. Below I have considered various interpretations of what is meant by a moral obligation, and have responded to each accordingly.

4.4.1 Or else!

Under this first interpretation of a duty, we consider that one must comply with moral duty or else they will face certain consequences. Within society, this may be some kind of punishment or damage to one’s reputation. Taking account of supernatural forces, this may include some kind of retribution in this life or the next. Here, the statement “You should not behave like that” is a claim that you will suffer the consequences.

By acting in accordance with this kind of duty or obligation one is acting in their own self-interest. The agent is motivated by a system or reward and punishment. Although their actions may benefit others, the reason for action is simply to avoid the negative outcomes which may come their way.

To claim that one should act in accordance with this type of moral duty is to use the conditional-should. In this case, the unconditional prescriptive epistemic modal fact states what the agent should do from an impartial perspective, while their so-called moral duty is to act towards self-preservation.

Because this interpretation of moral obligation does not involve the unconditional-should, it is not relevant as an objection to Moral Decision Theory. Disagreeing with a moral philosophy because it is not in your best interest is not a valid counter-argument.

4.4.2 Jiminy Cricket

A second understanding of moral obligation is the belief that some kind of normative force compels moral agents to act in a certain way. We feel guilt when we ignore our moral duties and pride when we do the right thing. Although in some cases, we may be better off acting in our self-interest, our conscience gets the better of us.

Someone who advocates for this version of authority would argue that some moral facts have authority upon us, because we have a strong internal moral compass which guides our behaviour. The moral claim that we should take Action X does not simply mean that X will have the best set of outcomes (as according to MDT). Instead, it means that we really really should take Action X.

This view of moral obligation is incompatible with the claim that morality is objective. While many of us may have a strong sense of right and wrong, it is not universal. Some people do not hold this feeling. Moral intuitions are subjective, in that they reflect the feelings or beliefs of an individual. While normative force may be something which some of us feel or experience, it cannot be said to be an objective feature of the world.

Further to this, it is necessary to highlight that moral facts are abstract. Abstract objects are generally supposed to be causally inert. This means that the moral facts themselves do not cause us to have any particular feelings of guilt or motivation to act. Because these feelings must be caused by something other than moral facts – we cannot rely upon those feelings to affirm the existence of moral facts. The most reasonable cause for the occurrence of such feelings come from our evolution as social animals and from an environment in which others act as though moral facts are binding.

Because this interpretation of moral obligation does not refer to objectivity, it is not relevant as an objection to Moral Decision Theory. Disagreeing with a moral philosophy because it does not match your subjective feelings is not a valid counter-argument.

4.4.3 Duty for Duty’s Sake

It might be argued that we should follow our moral duties simply because they exist. Under this interpretation, to believe that moral facts have some kind of normative force, is simply to believe that we ought to obey them.

This is to claim that moral laws are binding on us in the same way that natural laws are binding upon particles of matter. It is the view that moral laws exist within the fabric of the universe.

Someone who takes this view must still give a reason for why we should follow these laws of morality. When an apple falls due to gravity it does not choose to follow the law of gravity. In contrast, when a person follows a law of morality, they make a choice to do so. The analogy between these two types of law breaks down. The laws of nature define the workings of the universe, they do not govern it.

If there is no answer to the question “Why should you follow the laws of morality?” then those laws are essentially arbitrary. Following them only because they exist, means that there is no associated goal or benefit. An agent could choose to follow those laws, but such a choice is of no consequence.

Without any purpose behind it, these moral laws are not action-guiding. The statement “Doing Action X is consistent with Rule Y” is not even a prescriptive statement. It is not relevant to an agent’s decision because Rule Y has no benefit to them or anyone else.

Because this interpretation of moral obligation is not prescriptive, it is not relevant as an objection to Moral Decision Theory. Disagreeing with a moral philosophy because you have an arbitrary duty to do otherwise is not a valid counter-argument.

4.4.4 Because “I said so!!”

An alternative explanation as to the existence of moral obligation, is that we have been burdened with it by some authoritative entity. This view recognises that authority has an author.

For a set of binding rules or duties to exist, they must have been created by some entity. Within our everyday life, obligations are created by people themselves, either informally through norms of behaviour, or formally through institutions. From a religious or theological perspective, moral obligations are created by a supernatural being – typically God.

Under this view of morality, sometimes known as Divine Command Theory, to act morally is to act in accordance with the commands of God.

This definition of morality is conditional. The statement “You should do Action X” is equivalent to saying that “Action X is commanded by God”. However, one would only follow this commandment, on the condition that they believed in God, and wanted to honour God’s command. Without such a condition, an agent has no reason to choose Action X.

Because this interpretation of moral obligation does not involve the unconditional-should, it is not relevant as an objection to Moral Decision Theory. Disagreeing with a moral philosophy because it does not match your subjective goal of honouring God is not a valid counter-argument.

In response to the discussion above, at 4.4.4, some theists will respond that morality is not defined by God’s commands but by God’s nature. Under this view, God has the property of being omnibenevolent, or supremely just.

Someone taking this view will need to define “moral” in a way that does not simply refer to the attributes of God. For example, God is also understood to be supremely powerful, knowledgeable and intelligent. With the understanding that some of God’s characteristics are moral and others are non-moral, one cannot define morality as “A characteristic of God”.

4.4.5 Authority as a Guide

The final interpretation of authority refers to knowledge. Under this view, we don’t follow authority because of either fear or love, but simply because they know best. When an expert offers you advice, whether they are a doctor, an electrician, or a parent, you will take their recommended action because it is more likely to lead to the best set of consequences.

Under this interpretation, God has placed moral obligations upon people for a good reason. A definition of morality is not contingent upon God, but God acts according to moral standards. Further, God has commanded people to act morally for a particular reason. By acting in accordance with moral obligations, our actions will be in the best interests of those affected.

Because God has more information than a particular agent (some may believe that God has access to all the information) acting consistently with the laws of God will lead to the best set of subsequent events. This final interpretation of moral obligation does not necessarily contradict Moral Decision Theory. Just as one may logically choose to take the advice of a human expert, the correct choice in some cases may be to follow the laws or guidance of a supreme being.

However, to be consistent with Moral Decision Theory, two requirements must be met.

- The belief in the existence of God must be justified, such that it is the logical consequence of the information available to the agent.

- The belief that God’s moral guidance is known and understood must be justified, such that it is the logical consequence of the information available to the agent.

Debate on these two points is outside the scope of Moral Decision Theory. But it is important to understand that one can follow MDT whether they espouse or deny these two beliefs.

4.5 Indirect Objections

A final group of objections to Moral Decision Theory relate not to its truth but to its application. Some readers may have understood and accepted that there are moral facts, based on the information available to an agent, and yet they may still feel disinterested or unenthusiastic about Moral Decision Theory.

4.5.1 So What?

Someone might understand that the argument for Moral Decision Theory is reasonable, but much like a mathematical proof, they may feel it has no relevance to their actual life. They may be asking “Why should I care about the Moral Facts?”

This is really just another way of asking “Why should I care about other people?” When someone asks “Why should I care?” they are using the conditional-should. They are asking “How will I benefit by following Moral Decision Theory”. There is no answer to this, given that Moral Decision Theory makes no such claim. Subjective feelings about objective truths depend on the subject not the object.

In some cases, certain moral decisions will benefit the agent, but in others they won’t. In some cases, people will be motivated to make the moral choice, and in others they won’t. There are many facts about which we don’t care, but this is not an argument about their truth.

By analogy, consider a car. Moral Decision Theory can be considered as the steering system. Without reason, we cannot decide in which direction we want the car to move. There are right turns and wrong turns. We can make navigational mistakes or we can take the right path. If our steering system is faulty then we risk a serious accident. And if all the cars on the road are unable to steer then pile ups are inevitable.

But with only a steering wheel, the car goes nowhere. The engine of the car is our emotion. It is our passion, our desire, our empathy, our kindness and ultimately it is our motivation to act. These are admittedly subjective mental states which each of us will have in different proportions. However, as fundamentally emotional and desire driven creatures we need a motivational force to act.

In many cases, the individual who is more compassionate, who has greater empathy or perhaps who is less egotistical, will be more likely to make a correct moral decision than the more logical but apathetic individual. However, this shouldn’t be taken as evidence that decisions should be determined by our passions. The car needs an engine to run, but only the steering system is responsible for its direction.

4.5.2 It’s Just Too Difficult?

Another reaction to MDT might be that it’s just too difficult. The world is complex and dynamic and therefore we will never be able to determine the logical course of action. This might be true, but it is not an argument against the truth of Moral Decision Theory.

Regardless of the challenge at hand, it is still useful to recognise that there is a correct option. When applying MDT an agent can at the very least search for logical fallacies and internal inconsistencies within their own beliefs. When making judgments about the activity of others, we apply reason to evaluate their decisions and beliefs. Most importantly, two or more people can work together in the pursuit of truth, with a recognition that two opposing views can’t both be correct. Even when we cannot identify the absolute best option, we can still identify some options as better than others.

4.5.3 It’s Too Rational and Cold-Hearted

One perspective might be that because MDT is too logical to be the foundation of morality. A virtuous person is often described as kind, compassionate, empathetic or even courageous. We don’t often consider intelligence or critical thinking as moral virtues.

This position misunderstands Moral Decision Theory. Rationality is required to identify the correct choice, using logic to make predictions and to compare options. This is the case in any form of decision making. This could range from the selfish decisions made in warfare, or in commerce, to the selfless decisions made in medical treatment or in parenting. With other types of decision-making, the agent has an identified goal, and uses rational thinking to determine the best way of achieving that goal. With MDT, there is no goal, simply a determination of the valence and intensity of potential experiences.

Emotions are at the heart of MDT, given that the correct decision is the one which aims to reduce negative emotions and to promote positive ones. Further than this, empathy is important in providing information to the agent about how others will be affected by their actions.

4.5.4 It’s Too Arrogant and Confrontational

Some opponents may even go a step further and argue that Moral Decision Theory is at risk of doing great harm. By stating that morality is objective, one may conclude that certain people are objectively bad. Some may even conclude that certain cultures are better than others.

In the 20th century, totalitarian governments with extreme ideologies preached that they knew what was universally true. Based on their ideas of right and wrong, they worked towards utopian visions. This arrogant approach to morality meant that any opposition was violently and horrifically attacked.

This criticism would be a mischaracterisation of Moral Decision Theory. The claim that there is a right and wrong is different to the claim that one knows which action is right. An adherent of Moral Decision Theory will recognise that the task of determining which action we should take is vastly complicated, and often beyond our ability. In every decision, there must be humility, and acceptance that mistakes can be made. To properly apply Moral Decision Theory is to be open to new information and new arguments which may refine or revise our choices.

4.5.5 It’s Too Private

Each moral decision is dependent on a specific body of information which is available to an agent at a particular moment in time. The consequence of this may be that two people should act differently in the same situation.

Suppose that two people are walking together. Mary sees a large dog running towards a child. From her perspective, the dog looks dangerous and there is a risk that the child is in danger. Based on the information available to Mary, she should try to stop the dog and keep the child safe. Her friend Maggie recognises the child and the dog as her neighbours. She knows that the dog belongs to the child’s family and that there is danger. Based on the information available to Maggie, she should not intervene in any way.

Some may object to these seeming contradictions which occur within MDT. They may believe that morality is supposed to be a public exercise. They may take issue with MDT given our limited access to the information available to others.

While the private access to information is a feature of Moral Decision Theory it doesn’t preclude public discussions on morality and shared moral decisions. Whenever a group of people, whether a pair of individuals, a family, or an institution make a decision they must identify the body of information which they share. Upon this body of information, there is a correct decision to make. This includes decisions to create rules, policies or norms.

4.5.6 It’s Too Selfless

A final objection to MDT might be that it requires an unreasonable level of selfless or altruistic behaviour. Again this is a misunderstanding of the position, which requires impartiality but not selflessness. The key point to appreciate is the difference between impartiality in process and favouritism in output.

When applying MDT, no individual is favoured within the deliberation process. However, the output can and often will favour a particular individual. Every decision involves a trade-off between desirable subsequent experiences for some at the expense of others, and therefore the selected option will always favour at least one individual.

What is important to recognise is that even where an agent is impartial in their decision making, their decisions will actually favour themselves in the vast majority of situations. However, this is due to contextual or circumstantial reasons, not because the deliberation process itself favours the agent. Below, I give three explanations for why an impartial and unconditional decision will favour the agent themself in most cases.

Information Asymmetry

In most situations the agent will have more information about their own desires and interests than about those of anyone else. The integration of this additional information within the deliberation process will often result in an outcome which favours the agent.

Suppose that you wake up in the morning, you are hungry and ready for breakfast. However, you can infer that living on your street many of your neighbours are also hungry. Your available courses of action include the option of making breakfast for your neighbours. But of course, you don’t know what they want, you don’t know what time they like to eat and you don’t even know whether they’ll be appreciative of your gesture. So the potential consequences of making breakfast for your neighbours will probably be less desirable than if you just make breakfast for yourself.

Even though the agent does not prioritise their own interests over those of others, the outcome of a logical and impartial decision is that their actions will favour themself.

Hedonism and Relationships

There are certain joys and pleasures which are only possible when a person engages in self-directed action. We can dance but we can’t make someone else dance. If music is playing, it would therefore be logical to dance because it would lead to better consequences than if you attempted to get someone else to dance instead.

It is in our nature to simply enjoy certain experiences more when they are self directed. Anyone who has ever raised a child will know that at a very young age children get a strong desire to do things themselves. For example, they may prefer to get dressed themselves instead of being dressed by a parent, even when they find it slow and challenging. This human desire to do things for ourselves follows us into adulthood. Our lives have more meaning when we aspire towards certain achievements and we feel pride when we succeed.

Based on this recognition of human nature, it follows that certain actions should be self directed. Take sport as a prime example. If people acted selflessly, then all of us would be worse off. The overall joy and pride generated by sport would be greatly diminished if no one tried to win.

Our relationships with others also affect the intensity of subjective experience. Suppose John wants to buy a book as a gift for his friend. It might seem that to be impartial, he should find the person in his community who most desires that book and give it to them instead. This would ignore the positive subsequent experiences which occur from the nature of the relationship between John and his friend. John ought to decide to give the book to his friend, because of the additional desirable experience which results for both John and his friend from the gift exchange.

It is important to recognise that these reasons to act in one’s own interest emerge because of how the nature of human behaviour influences the nature of the consequent experiences. We could imagine an artificial intelligence or an alien species which behaves differently. For them, it might be that Moral Decision Theory would require acting selflessly instead.

Efficient Systems

Following on from the points above, we can consider that many of the systems, rules and norms of our society work best when people act in their own self-interest. The outcome of this self-directed action can actually be better for everyone than an alternative where everyone acts selflessly. It follows that the logical option can then be to act in your own self-interest even though your decision making is impartial.

In his book “Elements of Justice”, David Schmditz describes a hypothetical scenario as follows. A man is driving through a town for the first time when he is pulled over by a cop. The cop walks to the driver’s window, peers inside, and asks for the driver’s licence and registration. The cop shakes his head. “In this town, sir, we distribute according to desert. Therefore, when motorists meet at an intersection, they stop to compare destinations and ascertain which of them is more worthy of having the right of way.”

https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/elements-of-justice/desert/268B6C7A9B17949572933A4DAA0CAB09

This “Desert Town” where everyone is completely impartial might seem like the perfect place for an adherent of Moral Decision Theory to live. Everyone in town is diligent about making sure that their decisions favour whoever is most deserving. But it should be obvious that acting in this way is completely illogical. By stopping at every intersection to ascertain which driver is more worthy of having the right of way would slow everyone down to such an extent that any minor benefit is completely eradicated by the overwhelming cost. The system where drivers give way based on logical rules, rather than upon benevolence, is one which the adherents of MDT would actually follow.

In most forms of human interaction the correct decision is to act within a system or process which has already been developed. These systems might have been built around an assumption that people are selfish, but it could still be that an impartial agent should follow those systems.

Part 4 Code

Moral Decision Theory

In Constant Disagreement

An argument often levelled against Moral Realists is known as the Argument From Moral Disagreement. Individuals, groups and cultures disagree with each other about which actions are moral or immoral. The argument is that moral disagreement can be best explained by the view that moral statements either cannot be true (perhaps because they only express emotion), or that they are all false.

Some have even turned this argument around, suggesting that people wouldn’t argue so much about morality unless there was a fact of the matter. In a similar vein, people wouldn’t argue about the existence of God unless there was an actual answer to the question. Regardless, it is worth accounting for moral disagreement in the context of Moral Decision Theory.

Moral disagreement is most likely to occur because of either a difference in available information or because of a difference in reasoning. Usually, there will be a difference in both.

A good example of the difference in information is related to the sentience of animals. Many people, both today and throughout most of history, held the mistaken belief that animals do not experience pain. Someone who is taught this view, and who has no good reason to doubt it, will make certain decisions which ignore the pain and suffering of animals. However, a person who has learned of the current scientific consensus (that animals do in fact experience pain and suffering) will not.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pain_in_animals

Difference in information also comes in the form of experience. Someone who has experienced great hardship or suffering will have information that someone else doesn’t. This will result in them each holding different beliefs about choices which may affect the hardship or suffering of others.

The more common reason for disagreement will be that at least one side in the disagreement will have made a logical error. A simple example here is where a person holds the belief that people of their tribe, race, religion, nation, sexuality, gender or sex are of more value than another. This is not a justified belief. It is ultimately unfounded, and can only be held by someone who has engaged in biased or erroneous thinking.

Many decisions which people believe to be moral are actually determined on the basis of unjustified beliefs. We are all fallible. None of us has a perfect ability to reason, so it is entirely obvious that there will be moral disagreement.

Another way to look at logical fallacies is to consider the misapplication of moral rules, principles or norms. These may make sense in many cases, or may have been logical at the time of their creation, but people fail to apply them correctly.

An example of something which may have been reasonable under one context, but isn’t under another might be nepotism. In a hunter-gatherer society or a basic agrarian civilization, it would be perfectly reasonable (and therefore moral) for workers in a collective to be from the same family or tribe. The risk of relying on a stranger was too high. Despite the lack of fairness, this system would have had better subsequent experiences than any alternative. However, in the modern world, we have many institutions, laws, systems and technologies which allow us to trust strangers enough to employ them. Today, it would be biased, illogical and thus immoral to hire one’s family member over a more qualified candidate.

Moral Decision Theory makes a very compelling case for Moral Disagreement. Because of our different information, and our propensity for bias and logical fallacy, we should expect much disagreement between both individuals and groups.