Part 3 Prelude

Moral Decision Theory

In Other Words

As described above, Moral Decision Theory is a version of Decision Theory, in which all subsequent events of a decision are considered. There are no conditions placed upon a decision, which means that the agent’s desires, beliefs, goals or values are not taken into consideration. Because there are no subjective considerations, there is an objective fact about which decision the agent should make.

I have given this approach to moral reasoning the label “Moral Decision Theory” to place the conception of morality firmly within the mental activity of making choices. Other positions make claims about actions, while MDT makes claims about decisions. Other positions make claims about an agent’s intention, while MDT makes claims about the logical consequence of the agent’s information. Other positions make claims about what really occurs, while MDT makes claims about what options were available in comparison to each other. It is because of these perspectives that MDT operates in parallel to standard decision theory.

There is another label which I could have chosen for this approach. MDT could be understood as a version of consequentialism. As discussed in section 1.6.1, consequentialism is the position that determination of the correct action involves consideration of consequences. Using this umbrella term, we could re-name MDT as “Information-Relative Consequentialism”.

Information-Relative Consequentialism refers both to the occurrence of consequent events being determined by information, and to their properties being determined by information. Some readers may prefer this label because it feels intuitive, or because it fits within a strong tradition of moral philosophy. However, I have intentionally avoided this label to shift the focus from good or bad consequences to correct or incorrect decisions.

Generally, the view that consequentialism is objective includes the view that certain consequences have objective value. In contrast, Moral Decision Theory makes no such claim. There is no focus upon actual consequences of an action, only on the logic of the decision made. At the heart of MDT is the cognitive process known as decision making. This brings us to Part 3, which focuses on how to actually understand MDT in a practical sense. At this point we reconcile the theoretical prescriptive facts with the reasoning which agents use to identify them.

Part 3

Moral Decision Theory

In Practice

The implication of the central claim of Moral Decision Theory, is that a perfectly rational being, given a particular set of information, will be able to identify the best available course of action. However, humans are not perfectly rational. Our ability to identify the logical consequence of information is contingent on our ability to reason. We may also interpret information using intuition, imagination and empathy.

In this third part, I will discuss how human agents actually make decisions in practice. Here I will go into further detail regarding cognition, belief, uncertainty, experience and the use of reason. This will give clarification on Moral Decision Theory in the context of everyday decision making.

3.1 What is a Decision?

A helpful place to start this section is with the central term of the theory, “Decision”.

A practical decision is a cognitive process which occurs in the brain. It is the process by which an agent determines which action they will take. By analogy, we can consider another type of cognitive process, the performance of a mathematical calculation. Suppose you were asked to determine

1,735 + 9,856 – 3,440

In this case, you have a certain amount of available information, and you use reason to express the information in a simplified format. We can represent the cognitive process of doing this calculation as follows

Input: Information relating to the symbols and their meaning

Reasoning: Using logical thinking (mathematical ability) to add and subtract the numbers

Output: 8,151

A practical decision about how we should act in a certain situation follows a similar process.

Input: At the decision point, the agent has a certain body of information available to them. This includes information about their situation, and about the external world. This information is arranged in an extensive collection of beliefs.

Reasoning: There is a process of deliberation about the potential courses of action available. From the information available, the agent uses logic to determine the likelihood of potential subsequent events which may occur following each option. They must assess the relative valence and intensity of each potential experience which may occur.

Output: The output of this process is a determination of which course of action to select. The agent will identify a particular course of action which they believe to have the best range of subsequent experiences.

In both types of thought process (calculation and decision) a mistake can be made. It should be obvious that a person can make a mistake in performing a mathematical calculation, but it is also true of the practical decision. Suppose I am deciding whether to drink water or coffee. If I choose coffee, despite believing that I need to go to sleep soon, I have made an error in reasoning. Where the output of the deliberation is not the logical consequence of the inputs, the decision will not be the correct choice.

3.1.1 Decisions in Theory

The above outline of decision making is helpful to better demonstrate Moral Decision Theory. Considering inputs (section 3.2), process (section 3.3) and outputs (section 3.4), will allow a better understanding of how different elements of decision making relate to MDT.

However, it is important to understand that we are looking at ideal decision making, not actual decision making. We want to identify the optimal decisions which a perfectly rational agent would make. This will often be quite different to the decision which an actual agent will make.

We will not get sidetracked by philosophy of the mind, consciousness or even psychology. I am not an expert in these topics, so I won’t go further into how people actually make decisions, how they might make mistakes, or even into how decisions lead to actions. I am concerned with the abstract elements of logical decisions rather than with descriptive neuroscience.

3.1.2 The Boundaries of a Decision

To define and discuss a decision we need to be able to isolate it.

There are cases where multiple decisions are made about a similar course of action. Suppose Constance is considering which career they should pursue. This is something over which they deliberate for many years. We might think of this as a single decision, given that there is a consistent goal in mind. However, Constance will be consistently receiving new information over this period, so we should actually consider this as many separate decisions. On Tuesday, because they meet an inspirational accountant, they have new information which might make that seem like the best option. But on Wednesday, because Constance reads about accounting, then they will have information pointing in the opposite direction. Whenever there is new information, there can be a new best option.

We can use the term “decision point” to recognise the moment in which someone is engaged in deliberation. When new information is received, then there is a new decision point.

In other cases, multiple actions which result from a single decision. For example, suppose Stephen decides to walk up a flight of stairs. After he has taken the first step, does he then make another decision on whether or not to continue? Is there a decision at each step? Suppose he had decided to run up the stairs. Was there an initial decision about the direction of travel, and second decision about the speed, or was it only a single decision?

Although Stephen’s situation changes as he takes each step, he is not actually faced with any new information. So there is not a new decision point or a change in the best option. However, if he notices that the steps are slippery, or remembers that he forgot something downstairs, then there is a new body of information. This results in a different decision point and potentially a different best option.

3.2 Inputs

As described above, a decision is a mental process that begins with certain inputs. Central to Moral Decision Theory is the grounding in information available to an agent. Despite this, when making a decision, an agent doesn’t actually consider all of that raw information. We are simply unable to synthesise all of the available information, including all of our memories, at one moment. Instead, we make decisions using certain beliefs, which have been formed over time, generally on the basis of the information at hand.

3.2.1 Beliefs

A belief is a mental attitude or conviction that a particular proposition is either true or false.

Suppose that Tim is feeling thirsty and can see a glass of water on the table next to him. Tim holds the belief that drinking the water will quench his thirst. He doesn’t come to this belief through any consideration or deliberation at that specific moment. Instead the belief is based on previous experiences of being thirsty and of drinking water which go back to infancy.

In other cases, we might form new beliefs on the basis of those already held. Suppose that Tim notices that he is feeling more tired than usual, and that he hasn’t had a drink in a while. Upon further reflection of his situation, Tim comes to believe that if he drinks more water in the future he will be able to better maintain his energy levels.

3.2.2 Justified Beliefs

As discussed in 1.8.1

An Epistemic Modal Fact is

a Proposition which is a Logical Consequence of All Available Information

A belief is an individual’s subjective attitude regarding the truth of a particular proposition. Combining these two concepts, we can provide the following axiom.

A Belief is Justified if it Corresponds with an Epistemic Modal Fact

In the example discussed above, suppose that Tim was to look at the glass of water and form the belief that not only would it quench his thirst but that it would also make him invisible. This belief is inconsistent with the information available to him. Given that no glass of water has ever made him, or anyone he knows, invisible, then the belief in such an occurrence is contrary to the epistemic modal facts.

Given the exhaustive complexity of the world, and the beliefs we form about it, we will rarely be able to identify a complete map of each belief and the underlying information upon which it rests. Instead, we use intuition, heuristics, and mental shortcuts to quickly form approximate beliefs which are “good enough” for most situations.

Despite this opacity, where an agent has the time and desire to make correct decisions, then reflecting upon their beliefs is necessary. The agent can judge the consistency of their beliefs with the information available to them in order to evaluate whether or not those beliefs are justified. Any information which is inconsistent with their beliefs should be considered, and new beliefs formed. Any belief which is not founded upon information, or involves any logical fallacy, will lead to erroneous decision making. Where unjustified beliefs are used to decide upon a course of action, the decision is incorrect (or correct by coincidence).

3.2.3 Probabilistic Beliefs

In evaluating beliefs we are not concerned with whether they correspond with reality, but whether they correspond with epistemic modal facts. This is to consider whether they are justified based on the information available.

Tim looks at the glass of water, and forms a belief about whether it will quench his thirst. However, based on his visual perception, the glass could actually contain a toxic liquid like pure ethanol. It is an epistemic modal fact that there is a very small chance of this being the reality. That is, until he takes a sip and is presented with information which discounts this possibility.

If Tim was to believe, before taking a sip, that the glass was 100% certain to contain water, his belief would not be justified. Even if the glass does in reality contain water, this belief is not justified. Instead, recognising the limit of his perspective, a justified belief would be that the glass almost certainly contains water.

All of our decisions require us to form beliefs about the potential consequences of available actions. These all involve some level of uncertainty, which means that for the beliefs to be justified, they must reference probability.

3.2.4 Conditional vs Unconditional Decisions

In the majority of cases an agent will not be aiming to make a “moral” or unconditional decision. Instead, they will be aiming to determine the course of action which best satisfies their own desires, goals or values. In such cases, those desires, goals, or values may be considered to be inputs. The process of evaluating the potential subsequent events will involve comparison relative to those desires, goals or values. These desires, goals or values will provide criteria against which potential events are measured.

For these conditional decisions, a particular course of action will be best according to the selected criteria. If the agent has applied the correct logical thought process to the information available to them, and has correctly applied the selected criteria, then their decision is correct according to that particular condition. While the decision is objectively correct, it is correct according to subjective criteria.

Moral Decision Theory is concerned with finding the course of action which should be taken without reference to any conditions. For that reason, when applying Moral Decision Theory, the inputs exclude any frame of reference which is subjective. Desires, goals, or values are completely excluded from the decision.

3.3 Reasoning

We can now return to the decision making process which involves the synthesis of information and beliefs to determine which course of action is best. The main element of the decision making process is the logical thinking needed to determine how our potential actions will lead to potential outcomes. Through such reasoning, an agent will consider their options, and how these options may lead to a range of positive or negative experiences for the individuals affected.

3.3.1 Courses of Action

As discussed in Part 2, the first stage in making a practical decision is an assessment of which courses of action are available.

There may be situations in which an agent does not consider each of the available options, especially in cases where the potential list is exhaustive. In such cases, someone could still hold true beliefs in the form “Option A will be a better choice than Option B”, however they may be mistaken if they claim that “Option A is the best choice” where they have not considered “Option C”.

3.3.2 Subsequent Events

As mentioned in the prelude to Part 3, one might consider Moral Decision Theory to be a form of consequentialism. As stated, I prefer to distinguish MDT from consequentialism because it generally relies on the existence of objective values. The claim that certain consequences are objectively good is a claim that moral value exists as a feature of the real world. Alternatively, MDT only focuses on whether a decision is objectively correct without making any claims about the value of actual consequences.

We can better understand the distinction by comparing “Consequent Events” and “Subsequent Events”.

A consequent event is an event which actually follows as a direct cause of another. The simplest example would be one billiard ball striking another. The event of the white ball hitting the black ball, results in the consequence of the black ball moving towards the pocket. A single event can result in multiple consequences. Also, a consequence can occur because of multiple events.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/causation-metaphysics/

Moral Decision Theory is not concerned with the actual consequences of actions but with the potential consequences of decisions. While actions do lead to consequent events, what is important is how these events compare to the alternative set of events which would occur if a different course of action was chosen. MDT instead considers subsequent events.

Valerie is advised by her doctor to take medication for an illness. She is also advised by her friend to use chakra healing stones. Suppose that Valerie chooses to use the healing stones and her illness gets significantly worse. There is no direct causal link between the stones and her health. There is no mechanism by which the stones are causing Valerie to get sick. From a metaphysical perspective, her poor health is being caused by a pathogen which is spreading through her body.

Despite there being no direct causal link between Valerie’s actions and her poor health, in general conversation we would say that her refusal to take medicine has caused her to get worse. When we make this claim, we are not talking about the consequences of an action, but the consequences of a decision.

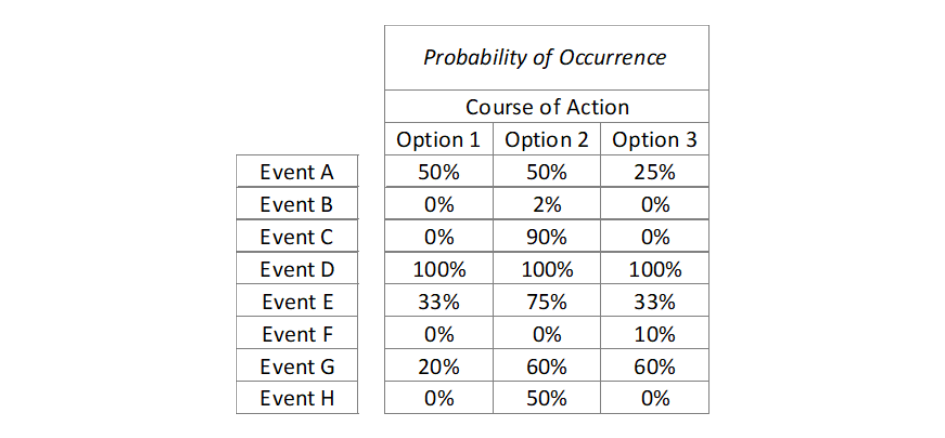

The concept of alternative subsequent events can be demonstrated by the following table.

For each event which could occur following a different course of action, there is a probability of its occurrence. The correct probability is a logical consequence of the information available to the agent. For most events (Event D in the example) the probability of occurrence is the same regardless of which action the agent takes. These events are therefore irrelevant to the decision. For others, the agent must take them into account to determine which is the best course of action.

The benefit of taking this approach is in that it treats action and inaction similarly. In the case of Valerie, ignoring her doctor will most likely be followed by poor health, while taking medication will most likely be followed by improvement. It is the comparison between these two options which results in one being correct.

3.3.3 Prediction

To identify the potential outcomes of our actions requires an agent to make predictions. As discussed previously, this is simply the reformulation or synthesis of the information which the agent has at hand.

Suppose that you reach into a bag of marbles, and can feel that there are 10 of them. You pull out five marbles, all of which are black. Will the 6th marble be black?

The probability is the logical consequence of the information available. You don’t know the colour of the other five marbles, so there are 6 possibilities.

- The bag initially contained 5 black, and 5 non-black marbles

- The bag initially contained 6 black, and 4 non-black marbles.

- The bag initially contained 7 black, and 3 non-black marbles.

- The bag initially contained 8 black, and 2 non-black marbles.

- The bag initially contained 9 black, and 1 non-black marbles.

- The bag initially contained 10 black, and 0 non-black marbles.

Given that you have retrieved five black balls, the final possibility is far more likely the first. You can use Bayes Theorem to calculate the relative likelihood of each possibility. And from there, you can calculate that the likelihood of the next ball being black is 85.7%.

Probability works in the same way when predicting the future. The information we have about past occurrences allows us to predict future ones – even the chance that the sun will rise tomorrow.

https://www.freecodecamp.org/news/will-the-sun-rise-tomorrow-255afc810682/

Of course, no human is capable of correctly analysing vast bodies of information with great accuracy. However, better reasoning applied to trends and observations will lead to better predictions. The aim is not to be perfect in our predictions, but to choose the correct course of action. Having our probabilistic beliefs be close to the epistemic modal facts will generally be sufficient.

3.3.4 A Range of Subsequent Events

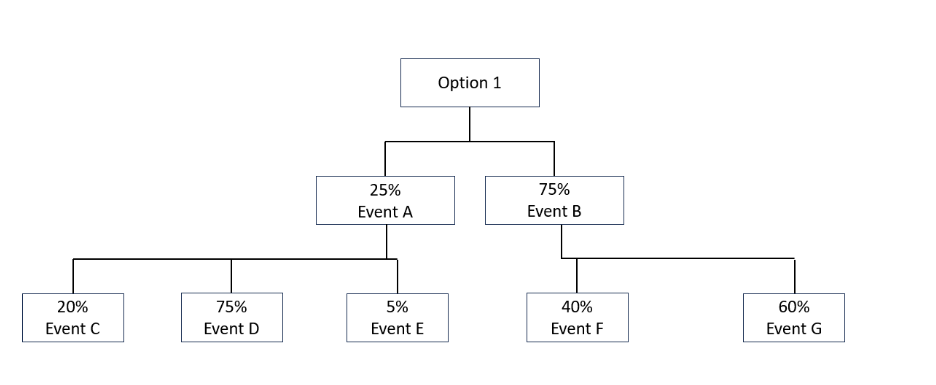

Following a decision point, there will be a chain of events which might occur from each available action. Of course each subsequent event could itself lead to a range of different events, each of which has an expected probability. We could imagine this as a continuous branching pattern which gets ever more complicated as more events are added to the tree.

From a practical perspective, the further and further down the tree these events go, the closer their probability of occurring gets to zero. There will be some events for which the chance of occurrence is similar regardless of which option the agent selects. This will be the case for most far-off and unlikely events. Because of the low probability, and the similar probability across the various available courses of action, these events are only rarely going to influence which option is correct.

Instead, those events which are more probable, and therefore which will have the greater variation amongst the available courses of action, will be those which the agent should be focused upon. It is the entire range of subsequent events which are taken into account when making a decision.

3.3.5 Uncertainty: Immaterial or Critical

We can never know anything about the external world with certainty, even through direct perception. What we can know are the contents of our own mind. For example, if I see a red box, I would not be justified in believing that there was in fact a red box. I can believe that “I am having the experience of seeing a red box”.

We also hold the belief that “Our perception can be illusory”. This belief will be based upon memories of situations where our perceptual experiences were contradicted later by others. The classic example would be viewing a straw in a glass of water. We perceive the straw to be crooked when in the water, but straight when out of the water. Given that these can’t both be true, we can conclude that at least one perceptual experience doesn’t correspond to reality.

A justified belief about the red box, derived from my perception of it, would actually be that “There is almost certainly a red box in front of me”. Because we believe that our perceptions can be wrong in very rare circumstances, but because we can’t determine whether our current experience is such an exception, we ought to take this into account. So a perfectly rational agent would hold no beliefs which expressed certainty about the external world.

From a practical perspective, we can often ignore this epistemic limitation as it will have no material impact on our decisions. In almost all cases, the decision will be the same whether we hold a belief about the external world to be 100% likely to be true or 99.999%. Our perception may not be perfect, but it is perfect enough.

Suppose that Tim believes there is a 99.999% chance that the glass in front of him contains water. Based upon this belief, the correct decision is to drink the water. In such cases, we can act as if we are 100% certain, because even accounting for the small probability of an alternative will not influence our decision.

However, in some situations, we should act in completely the opposite direction.

When visiting a shooting range, a common phrase of firearm safety is that “The gun is always loaded”. When someone makes this statement, they are asking people to act as if every gun they handle is loaded. By acting in such a way, people will avoid pointing the gun towards themself or someone else, thus reducing the risk of serious injury or death. The reason for acting as if the gun is always loaded is because the consequences of making a mistake are so serious.

In reality, when people believe that their gun is unloaded, they are almost always correct. Their belief that the gun is unloaded will be based on perceptual experience and memory. Yet in some very very small number of cases, the person holding what they believe to be an unloaded gun will, in reality, be holding a loaded weapon. So the justified belief of anyone holding what appears to be an unloaded gun would be that “This gun is almost certainly unloaded”.

Even though the chance that the gun is loaded may well be very small, because the negative impact of shooting someone is so severe, and because the desirable outcomes of pointing an unloaded gun towards someone are so immaterial, the logical decision is to avoid pointing the gun at anyone.

3.3.6 Subsequent Experiences

As discussed in Part 2, some of the subsequent events will be mental events – experiences. The agent will need to identify the nature of the experiences based on the information available to them. This includes information about the relevant stimulus and the disposition of the relevant individual.

The more information the agent has about the affected individual, the better they could reasonably estimate the nature and intensity of the potential experience. However, even with limited information, logic can still be used to approximate. From a position of ignorance the agent will have information about the typical individual. This is based on their own prior experience and memories of typical individuals.

The agent will therefore form beliefs about what type of experiences are likely or unlikely to follow from the different courses of action. These beliefs will be about the nature, valence, intensity and duration of each potential experience.

3.4 Output

After the agent has taken the relevant inputs, or beliefs, relevant to a decision and has used reason to identify the potential range of subsequent experiences, they must select the course of action which they believe to be best.

When an agent makes a conditional decision, perhaps based on their impulses or desires, the evaluation of which course of action to take will involve reference to those subjective preferences. However, to identify the best course of action, without any conditionality, the output will be impartial.

3.4.1 Attitude vs Desire

When considering a potential experience, an agent may have both an attitude towards it and a level of desire.

The attitude refers to their belief about the intrinsic goodness or badness of the experience itself. As a belief, it is a mental position about the nature of the experience. This belief is formed on the basis of other beliefs, and ultimately information in the form of memories. For example, if Karen believes that Experience A is good, then she believes that it is good regardless of to whom it occurs.

In contrast, a desire refers to an emotional state which describes the subjective position of someone at a particular moment. Suppose that one morning, Karen just doesn’t feel like getting out of bed. At that moment, she may not desire Experience A, even though she has a positive attitude towards it.

It is the attitude towards potential experiences which matters for logical decision making. Our current mood or feelings towards those experiences describes our subjective stance, but does not describe the nature of those potential experiences directly. A favourable or unfavourable attitude towards an experience is informed by our past.

3.4.2 The Veil of Ignorance

Agents will find it very difficult to make the impartial or unconditional decisions required of Moral Decision Theory. Our judgement of the best course of action will always be clouded by our self-interest, our values or simply our impulses and desires.

From a practical perspective, a method which aims to overcome our bias and selfishness is the “Veil of Ignorance”. In such a situation, the agent will determine which course of action is correct, without considering to whom the decision will affect.

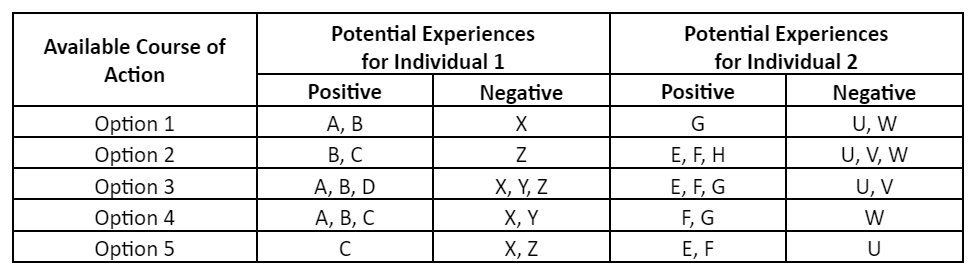

Suppose that two people will be affected by a decision. The agent will aim to identify the full range of subsequent experiences which they expect to occur following each course of action. They will identify those positive and negative experiences which will occur to each individual.

The agent would suppose that there is a 50% chance that they will have the range of experiences expected for Individual 1 and a 50% chance that they will experience those expected for Individual 2. They would engage in this process for each available course of action, and then determine which option they would prefer. The option which they have a more favourable attitude towards, given that they could face either set of experiences, will be the correct option.

The veil of ignorance approach allows the agent to conclude their deliberation and identify the “output”. This is the decision which they believe to be best. If the agent has followed a logical thought process, without any unjustified beliefs or without any reference to subjective criteria, then their selection will be correct. The course of action decided upon will be consistent with the epistemic modal facts.

An important point to note is that I am not advocating for a maxim suggesting that “You should use the veil of ignorance”. Instead, I am suggesting that using the veil of ignorance is a useful methodology for an agent to identify the correct action.

3.4.3 The Simple Version

While the above explanation, and previous sections, are very detailed and perhaps pedantic, adhering to Moral Decision Theory is not really that complicated. In essence, MDT in practice can be summarised as “Do unto others as you would wish done unto yourself”. It is essentially just the process of making impartial decisions.

Of course, this shouldn’t be particularly surprising. This approach to morality appears across history and across cultures. It fits our basic intuition, and can be explained to a child. What I hope that I’ve done here is to ground this “Golden Rule” in logic which is objective, rather than in either religion, in tradition, in our intuition or in any notion of tit for tat self-interest.

3.5 Other Practical Considerations

Up to this point, Part 3 has explained how we are to identify the best course of action, according to the information available to us. This general framework of input, reasoning and output will be enough to begin applying MDT to both everyday decisions and to challenging moral dilemmas. However there are some further points of clarification which may be helpful to the reader.

3.5.1 Decisions About Information

There is an important question to be answered about whether more information will lead to better decisions. In Parts 1 and 2, I explained that there is a logically correct decision to be made which is dependent on the information available to the agent. Gaining further information may change one’s decision, and lead to better subsequent events, but it does not render the earlier decision incorrect.

Suppose Clarence is looking after his sick child. He doesn’t know what her illness is and doesn’t know the cure. Without more information, the logical choice would be to give her rest and nurse her as best he can. However, he could also decide to get more information. He could seek the expertise of a doctor or pharmacist which is most likely to lead to better consequences. So while it’s true that the correct decision is dependent on the information available, it is often the correct decision to seek more information.

In alternative situations, particularly those with time pressure, seeking further information may not be the correct course of action. The opportunity cost may be too great.

3.5.2 Decisions About Decisions

Given that an individual does not possess the power of perfect reason, they are limited in their ability to determine the correct answer. It follows that in the majority of cases, the longer that a person deliberates for, the more likely they are to select a better option. The cognitive process of decision making takes time, and additional time can lead to improved analysis of potential consequences or even the identification of previously unconsidered options. With any decision, the agent could potentially engage in a meta-decision about how much time they should spend on the decision itself.

This decision about how long to spend in deliberation follows exactly the same logic as any other. The cognitive process of decision making is an action in and of itself. The agent should consider the potential consequences of further thought, i.e. how important is it to get the underlying decision correct, and what are the potential negative consequences of taking the additional time?

3.5.3 Experiences of Non-Humans

The astute reader will notice that the word “human” has not appeared in the text to this point. Moral Decision Theory states that the best course of action to select is the one which is expected to result in the best experiences for those affected. Best is to be interpreted as referring to the intrinsic property of experience itself.

A rock, a table or a summer breeze cannot experience. For this reason, a logical decision does not consider how events affect such objects. An action might move a rock, break a table or re-direct a summer breeze, but these events are neither good, or bad. That is because those entities have no ability to experience. The events described do not have the property of goodness or badness.

The kinds of entities which can experience are those which are sentient or conscious. This group includes all but the simplest of animals, and therefore a logical decision which affects an animal will take their subsequent experiences into account.

This requirement to consider the experiences of animals should not be interpreted as the proposition that a human should be given equal importance to an animal. A moral theory which assigns value to either humans or animals is one which relies upon value. However MDT rejects the existence of objective value and instead is grounded upon valence.

MDT takes account of experiences without regard to whom those experiences occur. What this means for animals is that we need to consider their experiences, but with the understanding that the nature and intensity of their experiences will be determined by their cognitive ability (their disposition). While we may have extremely limited access to the minds of non-human animals, we can form justified beliefs that greater cognitive ability leads to more intense and more sophisticated experiences.

Suppose an agent has a choice between inflicting physical harm on a slug and inflicting physical harm on a chimpanzee. The best option is determined by the agent’s attitude towards the subsequent experiences. In turn, those potential experiences are determined by the agent’s information about the relevant individuals. In this case, the agent will have information regarding the relative size and complexity of the mind of each animal.

Suppose the agent were given the choice of either experiencing the same level of pain expected to be felt by the chimpanzee or the same level of pain expected to be experienced by the slug. They would choose that of the slug. This choice is based on their justified belief that the pain will be less intense and perhaps shorter-lasting for the slug. The agent’s attitude towards the consequent experience of harming the chimpanzee is more negative, which means that the logical option is to harm the slug.

So we can take into account the effect of our actions on non-human animals in the same way that we would for humans. How we determine the nature and intensity of the subsequent experience will depend on the individual affected. The experiences for animals may be different to those for humans, but these experiences should be compared in exactly the same way.

Another sentient being which we may soon have to consider in our decision making are artificial minds. There will of course be an epistemic challenge in determining if and how artificial minds can experience. But this uncertainty does not mean that a logical decision cannot be made.

A final category or perspective on those which might experience, is the consideration of individuals which do not yet exist. This could of course include humans, animals and artificial minds. When we talk about potential experiences, and we disregard to whom they are to occur, then it is logical to include in our consideration those who do not yet exist.

3.6 Out of Scope

When explaining a philosophical position it is also important to identify the claims that are not being made. Readers, or more likely those who do not read the entirety, may assume that MDT covers related topics within moral philosophy or within decision theory. The sections below aim to clarify those areas which are out of scope.

3.6.1 Motivation

Moral Decision Theory refers to the identification of the correct course of action, without reference to any subjective desire or emotional state. In contrast, motivation to act in a certain way comes directly from their subjective desires or emotional state. These two concepts are correlated, but they have no causal connection.

There are many factors which motivate an agent’s decision to choose a particular course of action. While some may have a desire to act in accordance with what is best from an impartial perspective, it is not a common feeling or something that is intrinsic to human nature. Even those who act from compassion, empathy or altruism are not necessarily motivated by what may be the objectively best course of action. MDT can be used to identify whether a person’s actions are in accordance with what they should do, but it cannot motivate them to do so. Ultimately, an abstract concept, such as a moral fact, has no causal power.

3.6.2 Free Will

Another worthwhile point of clarification revolves around the interaction between MDT and Free Will. As decision making is central to both, one’s beliefs about one might influence their beliefs about the other. However, this is not necessarily the case. Moral Decision Theory is compatible with both a belief in free will and with a denial of it.

If one believes that rational agents have the ability to make free choices, then it is consistent to also believe that we should make a particular choice. A proponent of free will can also believe that there are epistemic modal facts about which course of action is best.

That MDT is also compatible with the denial of free will, may require further explanation. To understand this, requires the reader to differentiate between metaphysical modality and epistemic. A denier of free will believes that the choice of an agent is determined by prior circumstances. This claim, or the belief in determinism, is the claim that the agent could not have chosen otherwise. This is a position regarding metaphysical modality. It therefore has no relevance to Moral Decision Theory.

MDT makes the claim that for every practical decision, the correct choice, or a best course of action is contingent upon the information available to the agent. This is a claim about epistemic modality.

Someone who denies the existence of free will, but who accepts MDT, will recognise that in some cases an agent should take a particular course of action, despite the fact that they are pre-determined to take another. The fact that an agent is motivated to act in their own self-interest, does not negate the fact that they should act otherwise.

3.6.3 Autonomy & Freedom

All of our “moral” decisions affect other individuals. Whenever an agent makes such a decision, especially where others experience negative outcomes, a question might be asked about what right the agent has to take such an action. In some cases, our decisions may limit the options available to others, which can be understood as affecting their freedom or their autonomy. Given that decision making is at the heart of Moral Decision Theory, it is reasonable to explain how MDT applies to decisions which affect the decision making of others.

The starting point is the recognition that autonomy has no objective value. As discussed previously, and defended in Part 4, MDT does not rely on the existence of any objective values. For that reason, autonomy, liberty or freedom is not considered to be a necessary or integral element of MDT.

Despite accepting that autonomy has no inherent value, it will often be the case that actions which respect or promote the autonomy of others will be correct. In the majority of cases, other individuals are in a better position to decide for themselves, than an agent will be. The implication of this is that the best course of action will be to leave such choices to others. As others are better informed about their own disposition, the likelihood of better outcomes is increased when individuals decide for themselves.

In addition to the immediate positives of letting individuals make their own decisions, there are also longer-term benefits. Individuals who make their own decisions will be able to improve their decision making abilities over time, and will also experience the positive feelings associated with independence and freedom.

On the other hand, there will be many cases where other individuals are unable to make their own choices, or where they are likely to make bad decisions. In such cases, an agent should take whichever action is best, even if this means limiting the freedom of others.

There is a complex and nuanced balance regarding such situations. These will be discussed further in a later section.

3.6.4 Immoral Thoughts

As explained in Section 1.2.1 Moral Decision Theory only relates to practical action. The implication of this is that under MDT we cannot make judgements about someone’s thoughts. Is it objectively wrong to imagine evil, horrific or discriminatory things?

Where we can apply MDT to such thoughts is in reference to how they may lead to decisions in the future. Violent or subversive thoughts may increase the likelihood that an agent will make unethical choices.

We can also differentiate between intrusive thoughts, which passively occur in the mind, and deliberate thoughts, which we choose (in some sense) to have. A decision to have violent or discriminatory thoughts can therefore be objectively wrong, even if there are no direct outcomes. Even when not directly faced with a decision, we can choose to improve our beliefs and desires to bring them in line with moral behaviour.

Part 3 Coda

Moral Decision Theory

In The Same Boat

Having read through these first three parts, the reader may find that a sound argument can be made for prescriptive facts. However, the reader may also find that the application of these facts to our decisions is too difficult or is simply not relevant.

Most of our decisions can be described as quick and instinctive. We don’t have the time to engage in lengthy deliberation, and consideration of every single possible option and every single possible outcome. Some may find that MDT is simply too challenging to have any place in their lives.

Further to this, our decisions are generally self-directed, or conditional upon our desires to benefit those whom we love and care about. Moral Decision Theory prescribes impartial decision making, which readers may feel is not applicable to their everyday choices.

Such a dismissal of MDT misses the point. The primary claim of MDT is that there is a correct decision which can be made without reference to any subjective value, belief, desire or opinion. Acceptance of this claim will allow agents to engage in deliberation to determine which course of action is best.

Importantly, when two individuals accept this central claim, they can engage in rational conversation to find a common understanding of which action or behaviour is correct. By discussing our disagreements within the context of Moral Decision Theory, we can better understand each other, and seek to resolve conflict. Our disagreements may arise from differing information, or different reasoning, but they will occur because of different values or different systems of morality. Where two people both agree in unconditional prescriptive epistemic modal facts, they will find common ground upon which to build a collaborative approach.

When a group of people can agree with the central claim of MDT, they can begin to make decisions at the group level which take into account the potential experiences of everyone, both inside and outside of their group. This can enable discussions within those groups, and their institutions, to focus on rational decision making. Without adherence to MDT, arguments within groups will be stuck focusing on subjective ideals and values – which cannot be resolved without force.

The primary reason for me to write about, and to explain Moral Decision Theory is to gain common understanding and consensus on the possibility of making objective decisions. Groups of people must have this shared understanding for them to make truly shared decisions.