Part 2 Prelude

Moral Decision Theory

In More Detail

In Part 1 I have given a comprehensive account of how key terms will be used in relation to Moral Decision Theory. After laying this groundwork, I can give a more detailed explanation of the position.

Central to the theory is the link between information available to an agent and the best course of action which they are able to take. It is important for the reader to understand that this link has no dependence on the desires, beliefs, goals or values of the agent. More importantly, it has no dependence on the actual consequences of the decision or even upon the actual state of affairs in which the agent exists. Instead, the correct action is a logical consequence of the information available to the agent at the moment of making that decision.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/logical-consequence/

Every agent has a body of information which includes their memories and perceptual experience. The logical consequence of this information is that certain actions will result in a range of possible events. The probability of occurrence for each event, and an account of its properties, are entirely contingent on the available information.

Suppose that Jenny observes that there is a pot of water sitting atop her kitchen stove. She could choose to turn the stove on, or not. Jenny has information about the current situation, and also about the nature of water and heat. It is an epistemic modal fact that “If Jenny turns the stove on, the water will be more likely to boil.” This is a fact about a potential event which may occur subsequent to her decision.

Some subsequent events are mental events. These occur within the mind of an individual, and include experiences such as feelings, emotions, attachments, or moods. Just as described for non-mental events, the occurrence of potential mental events is dependent on the information available. The properties of the potential mental event are also determined by the agent’s information, particularly memories of similar events.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mental_event

Now suppose that Jenny, as described above, observes that the pot of water is bubbling and steaming. She has a choice of whether to submerge her hand in the boiling water or not. Jenny has information about the experience which results from exposing skin to boiling water. The logical consequence of this information is an epistemic modal fact that “If Jenny places her hand in the water, she will experience intense pain”.

The potential subsequent mental events could be either positive or negative. They could either have a strong or mild intensity. Different potential experiences can be compared to one another by their relative intensity, meaning that some potential experiences are better or worse than others. Better and worse refers to the valence and intensity of the potential experience, not to any sense of either objective value or subjective preference. Potential experiences have the intrinsic property of being good, meaning that one can be intrinsically better or worse than another.

A course of action will lead to a range of subsequent events, including many potential experiences. The range of subsequent experiences from one course of action can be compared to those of another. The logical consequence of such comparisons is that of all options available, one particular course of action will lead to the best range of subsequent experiences.

Following from the definitions which have been clarified in Part 1, to claim that a particular course of action will lead to the best range of outcomes, is equivalent to the claim that an agent should choose this course of action. This is an unconditional prescriptive epistemic modal fact, and in some cases, may be defined as a moral fact.

Part 2

Moral Decision Theory

In Principle

As explained above, the central claim of MDT is that some unconditional prescriptive propositions can be objectively true. In Part 2 I will present an argument which seeks to demonstrate and prove this central claim. The implication of this claim is that for any decision, there is at least one course of action which is best.

Given the immense complexity of our lives, in most cases an agent will not have the reasoning capacity, or perhaps the time, to identify which course of action is best. However, at this stage in the presentation of MDT, we are not concerned with determining which course of action is optimal, only with determining that there is such an optimal option.

A helpful analogy is to consider a game of chess. At any stage in a game, a player has a range of options, at least one of which will be the most advantageous (see Zermelo’s theorem). We can intuitively understand that some moves are better than others, even if we are new to the game and have no idea how to work out which is which. A player will accept that there is a correct move, even if they lack the ability to identify it. The same is true of all decision-making.

This may seem like a bold claim. But consider yourself sitting outside on a sunny day, feeling uncomfortable from the heat. Would it be a good decision to put on a coat, a hat, gloves and a scarf? Such an action would be illogical. Given that logic is not dependent on subjective feeling, we can say that putting on warm clothes is objectively incorrect.

In Part 3, we will start to consider how we might make decisions given imperfect abilities of reasoning. Until then, we are simply interested in proving that for each decision, there is a correct course of action. To do that, I will work through 14 premises which build an argument towards this conclusion.

At each stage in the argument, we will consider a decision faced by Angie. She is walking by herself one day when she notices a child drowning in a river. We will investigate the proposition that “Angie should try to save the child?” and determine whether or not this is a prescriptive fact.

If this is a fact, then Angie is wrong if she denies its truth. For Angie to make an opposing claim that “She should not try to save the child” would not be a matter only of opinion, but would involve a logical error. As we identify each relevant fact of the situation, I will identify how an error could be made, demonstrating the difference between objective fact and subjective opinion.

2.1 Subsequent Events

The initial claim of the argument for Moral Decision Theory is that in any situation there are epistemic modal facts about what events may follow the different courses of action available to an agent. The probability of each subsequent event occurring is a function of the information available and the particular course of action chosen.

Premise 1: The agent has information about their current situation

Premise 1 follows from the fact that the agent is a sentient being, with the capability of perceiving the external world. Different agents will perceive actual objects and events differently, depending on their capacity and their prior experience. Because of this gap between perception and reality, the agent will not have direct access to actual facts (those which refer to the external world). However, there are objective facts about the perceptual experience itself.

Angie is walking by a river when she notices a child who appears to be drowning in the river. Angie looks around to see if anyone else is around who might be able to save the child. She doesn’t see anyone.

Even if there is actually someone there, hidden from view, it is an objectively true fact that Angie perceives that no one is around. If someone else was to claim that Angie saw the other person, they would be incorrect.

Premise 2: The agent has information about past events

The agent will be informed by their memory. This includes memory of previous perceptual experiences which can be labelled “episodic memory”. It also includes “semantic memory” which refers to recall of propositions, for example “I remember that there are 30 days in the month of June”. The agent will not be certain about which of their memories correspond to actual facts about the external world. However, there are objective facts which directly refer to those memories.

Angie has memories of swimming and being in water. This will not correspond exactly to the events being remembered. She has information about oxygen, the respiratory system, and about floatation. Some of this information may not be factually correct and some may be false. Regardless, it is objectively true that Angie has these memories.

Premise 3: Based on the available information, certain subsequent events could occur. The probability of each subsequent event occurring is a logical consequence of the information available.

Premise 3 is inferred from Premises 1 and 2

A decision requires consideration of how an agent’s actions may affect future circumstances. Information about previous events informs which potential events could occur in the future. As defined in Section 1.8.2, the probability of future occurrence is determined by the information about past occurrences of similar circumstances.

It is important to note that two different individuals will have different available information. The probability of subsequent events occurring will be different for each individual, resulting in two different epistemic modal claims. Despite the two claims being different, both can be objectively true, because both reference a different body of information. There can be differing epistemic modal facts because they are formed of different epistemic perspectives.

Conclusions can be drawn from Angie’s perception of the situation, and information she has about the inability of humans to breathe underwater. The logical conclusion of her available information is that it is very likely that the child will drown.

Suppose that Angie was to conclude that a miracle was imminent, and that the child will be fine. Such a proposition would be incorrect. She has made a logical error because this claim is inconsistent with the information she has at hand.

Premise 4: At the decision point, an agent could choose different courses of action

Premise 4 follows from the fact that the agent is a sentient being, with the capability of performing the cognitive process that is decision making. If a being cannot make such a choice, then they are not an agent.

We are concerned here with practical decisions which are the deliberative process by which an agent selects a course of action. A “course of action” refers to a series of coordinated actions. For example, consider donating to someone who is begging for money on the street. This may involve taking out your wallet, opening the wallet, grabbing the coins and handing over the cash. Even simple “acts” such as donating money could be considered to involve multiple individual actions.

Which actions are grouped into a set (course of action) will be dependent on the situation. If one particular choice commits the agent to taking all actions within the set, then they can be considered within the same “course of action”. However, if there is expected to be another decision point before all of these actions are taken, then only those which will occur before the decision point are considered part of the “course of action”.

One decision point is separated from another by a change in the information available. If new information becomes available to the agent, the facts affecting the choice have changed.

Another reason to decide between courses of action as opposed to between separate actions, is that inaction is understood as a course of action. Sometimes the correct decision is to take no action at all.

For any decision, there are epistemic modal facts about which options the agent could choose.

Angie knows how to swim. One option available to her is to dive into the water in an attempt to rescue the child. Another option is to call for help, in the hope that someone else is able to come. Yet another option is to ignore the situation and continue with her morning walk.

Premise 5: Each available course of action will lead to a different range of subsequent events

Premise 5 is inferred from Premises 3 and 4

A potential course of action, available to the agent, is itself a potential future event. This event can be expected to lead to future events based on the information available. Even if the agent chooses not to act, then a different range of subsequent events can be expected to occur.

A range of events includes all which could occur, weighted by probability. Suppose that Event A has a 50% chance of resulting in Event B and a 50% chance of resulting in Event C. Event B has a 75% chance of resulting in Event D and a 25% chance of resulting in Event E. And so on. All the potential events, and their relative probabilities, are considered to be included within the “range”.

It is worth noting that no human can ever conceive of the entire range of subsequent events. The magnitude and complexity is far beyond the cognitive ability of a human. Despite this epistemic challenge, there are still logical consequences of the available information.

If Angie dives into the water, there is a good chance that she can rescue the child. There is also a small chance that she herself will struggle in the water, and she may drown.

If Angie’s fear of drowning were to impair her judgement, she may conclude that her risk of drowning was significantly high. This belief would be untrue – it does not correspond to the epistemic modal fact.

Recap

The agent has information regarding perceptual experience of their current situation, memories of events (including experiences) and the available courses of action. The logical consequence of this information is that

- Each course of action will lead to a different range of potential events.

An objectively true epistemic modal claim can be made about which events could occur, and with what probability, following a particular choice.

2.2 Mental Events

The next stage in the argument refers to mental events. According to Moral Decision Theory, some mental events are good or bad. As discussed in Part 1, this does not refer to any value which supervenes upon the mental event, but to the intrinsic nature of the experience itself.

Premise 6: Experiences are mental events, which have intrinsic properties of nature, valence, intensity and duration

Premise 6 is understood by sentient beings through reflection of their own experience. In this context, an experience could be a feeling, emotion, attachment, or mood.

The nature of an experience can be understood in reference to others which are similar or different. For example, we might say that one experience was grief while another was joy. The classification of experience is subjective, and there are no distinct categories upon which objective statements can be made. I will refer to the nature of experience, but not rely upon it to form any facts. What matters for Moral Decision Theory is the valence, intensity and duration of an experience.

Valence refers to whether an experience is good or bad. A sentient being will perceive some experiences as good, and others as bad. The terms good and bad refer to the internal experience of the individual subject, and are not in reference to any external measure. There are neutral mental events, such as perception of colour, but these are irrelevant to a decision.

Valence is a separate property from the nature of the experience. For example, we usually think of anger as a bad experience, however, there could be circumstances where it is good. There is no direct correlation between nature and valence.

Intensity refers to how positive or negative an experience is. A mild discomfort will have a low intensity, while a deep and sharp pain will have a high intensity.

Duration refers to how long the experience lasts. Given that experience lasts for a period of time, we can consider it to be an event. Because it is an event, we can also consider it to have a cause, and for the experience to have a causal impact on other events.

Premise 7: The nature, valence, intensity and duration of a mental event is caused by the stimulus and the disposition of the subject

Premise 7 is understood by sentient beings through memories of their own experience. As with any other contingent event, the mental events defined as experience, are caused by prior events.

Experience occurs within the mind of sentient beings in response to external stimuli. This could be a physical event, such as touching a hot stove or a more complex situation such as winning a gold medal or being insulted by a loved one. It could also be an aggregation of multiple real-world events which determines the nature, intensity and duration of an experience.

Experience is also dependent upon the disposition of the mind in which it occurs. Suppose that someone is exposed to a spider. If they have a fear of spiders, then the subsequent mental event is that they experience great anxiety and stress. However, it might be the opposite if they are fond of spiders.

Disposition can be understood as a very general term encompassing all properties of a mind at a particular time. This includes the complexity and capability of the mind, the likes and dislikes of the mind, and the mood and emotional state of the mind.

To discuss the various facts and opinions regarding subjective experience, it is helpful to introduce some symbols.

Let S represent the external stimulus which causes the experience.

Let D represent the disposition of the individual affected by the stimulus.

Let E represent experience itself.

We can then say that the properties of experience E are a function of S and D.

If two individuals, Dan and Dani, have dispositions D1 and D2. They are exposed to stimulus S1. We could label the resulting experiences as E1-1 and E2-1 respectively. We could also consider that a single individual might have a different disposition on Monday than they do on Tuesday, and therefore have two different experiences despite the same stimulus.

Were Angie to dive into the water, she might feel cold. The associated discomfort would be a function of both the temperature of the water and her personal tolerance level for cold environments. Were Angie to walk past the drowning child without helping, she might feel guilt, which is a function of the situation and her empathy.

We can also consider the experiences of the child. If Angie were to save him, he would feel relief and elation. If he were to be ignored, he would feel the agony of running out of oxygen.

Premise 8: The nature, valence, intensity and duration of a mental event is distinct from the subject

While the properties of an experience are caused, in part, by the disposition of the subject, they are distinct from the subject. Understanding of this premise allows us to conceive of experiences directly, and to make objective claims about them.

Suppose we want to know if someone likes pizza. We can look again at our symbols. The stimulus event of eating pizza is Sp. The positive experience of enjoying it is E➕. The unknown variable is Dx. If we make the claim that “Bob likes pizza” we are making a claim about the disposition of Bob (Db). The claim “Sp+Db = E➕“ means that if Bob eats pizza he will have a good experience.

Consider the claim that “Bob likes the good experience which occurs when he eats pizza”. This claim means that if Bob has a good experience, he will have a good experience. It effectively says nothing at all. It doesn’t make any reference to either a stimulus or to Bob’s disposition. It is only a claim about the experience itself.

Suppose we define experience Ex as having a certain set of properties, including that it is bad. Different individuals have different dispositions, so for them to experience Ex they will need different stimulus. However, if they do have this experience, it will be bad for each of them. It is impossible for someone to enjoy Ex because enjoyment is a different experience from Ex.

It may help to consider as an analogy – the experience of perceiving colour. Brightness is a property of the mental event of visual perception. It is caused by both an external stimulus (the luminance of an object in its environment) and the disposition of the observer (their visual system). Two different individuals may perceive the same level of brightness, despite them looking at different objects, and despite them having different visual systems.

The discomfort which Angie experiences from being in cold water has a negative valence. It is not bad because Angie believes it to be. Instead, Angie believes that the discomfort is bad because she perceives it to be. She perceives the badness through having the experience.

Someone might claim that Angie’s experience of discomfort was only subjectively bad. They may argue that describing the discomfort as bad is a description of Angie’s subjective preference. This would be a logical error. It is Angie’s subjective response to cold water which causes the bad experience. However, Angie doesn’t have any subjective response towards the discomfort itself.

2.3 Potential Mental Events

The third stage in the argument is to demonstrate that the goodness or badness of potential mental events is information-relative. While many moral theories make reference to the value of actual events or experiences, Moral Decision Theory is only concerned with potential experiences which are defined by the information available to the agent.

Moral Decision Theory relies upon the claim that potential experiences can be better or worse than one another. This comparative intensity is contingent upon information.

Premise 9: Based on the information, certain mental events could occur. The probability of each subsequent mental event occurring is the logical consequence of the information available

This is simply a more narrow phrasing of Premise 3. Following on from Premises 6 & 7 it is worth discussing that epistemic modal facts can refer to mental events.

The agent will have information about the potential disposition of individuals. The agent will have information about the potential stimulus events which could occur. And the agent will have information about the potential experiences which could occur from the interaction between disposition and stimulus.

True statements about potential events involve probability. It is no different with regard to mental events. An agent may have memories of a particular event, of their disposition and the resulting experience. The logical consequence of this information is that similar future situations will lead to similar experiences in the future. There is a chance that the experience will be more or less intense. The logical consequence would be a probability distribution determined by the empirical evidence of past experience.

The experience of discomfort is something which could occur, given the information available to Angie. It is a potential mental event, which is likely to occur if Angie chooses to dive into the river.

If Angie was to conclude that she would not feel discomfort, this would be illogical. Her belief would be unjustified, and factually incorrect.

Recap

The agent has information regarding perceptual experience of their current situation, memories of events (including experiences) and the available courses of action. The logical consequence of this information is that each course of action will lead to a different probability distribution of events (including experiences).

There are epistemic modal facts about the properties of these potential experiences.

Premise 10: Remembered experiences are mental representations of experiences, with nature, valence, intensity and duration

As discussed previously, epistemic modal claims depend on the information available. This information includes memories of experience and the stimulus and disposition which caused them.

Remembering an experience and having an experience are both types of mental events. However, they are not equivalent to one another. The memory is a representation of the actual experience.

Premise 11: Remembered experiences can be better or worse than one another

Premise 11 is inferred from Premises 8 & 10

Given that remembered experiences have valence and intensity, it follows that one could be better or worse than another. This seems obvious when comparing experiences of the same nature. For example, torturous pain is worse than a minor injury. To understand how this premise can be true for experiences of a different nature, we need to dig a little deeper.

It is true that different types of experiences cannot be measured against a single scale. Try to compare an intense sharp pain in the foot which lasts a few minutes with a deep sense of anxiety which lasts a few weeks. We cannot give the first a Suffering Score of 62 and the second a Suffering Score of 78 and thus determine that the second is objectively worse.

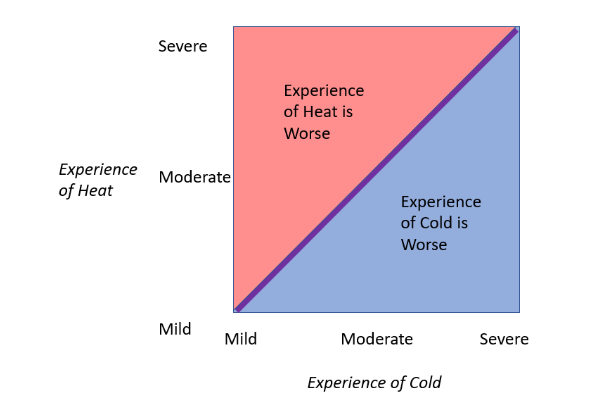

Despite this, individuals can still perceive which remembered experiences are better or worse. Suppose you were to compare two types of discomfort, such as feeling too hot and feeling too cold. You would identify that the pain following severe heat was worse than the discomfort from mild cold. You would also identify that severe cold was worse than mild heat. At certain levels of discomfort, you would be indifferent. We could visualise this through the diagram below.

An agent could consider two remembered experiences, one of feeling hot and another of feeling cold. The agent will perceive which memory left a greater negative impression upon them. Their conception of one memory will have a greater intensity than another.

It is tempting to suggest that one person may have a preference for feeling hot or cold. However, this disposition has already been taken into account to define the intensity of the experience. Recognise that the axes of the diagram above represent experiences themselves, not stimulus. If these axes show temperature, the line will have a different shape, but that is not the case when comparing experience.

Someone may claim that they prefer a moderate cold discomfort to a moderate heat discomfort. However, this is a nonsensical claim. The intensity of the experiences is a function of the individual’s disposition. If both are defined as moderate, then both have the same intensity and the agent is indifferent towards them. If instead, the agent prefers the particular cold, then either it is actually “less intense than moderate” or the heat is “more intense than moderate”. As explained in Premise 8, experiences are distinct from the subject.

Essentially, a diagram representing a comparison of any two experiences with the same valence will have the same shape as the one above. To say that one experience is more intense than another is to identify that it is better or worse.

Angie’s decision rests on comparison between different experiences. She may have a memory of experiencing terrible grief. She may also have a memory of experiencing cold from being exposed to cold water. Based on the information available from these memories, she can conclude that terrible grief is a more intense negative experience than discomfort from cold water. This is the logical consequence of the information available to her, so any other conclusion would be incorrect.

Premise 12: Potential experiences are conceptual representations of experiences, with nature, valence, intensity and duration

A potential experience is a conceptual representation of an experience which could occur in the future. The concept is no different in nature to a memory of an experience, especially considering that we can conceive of a prior experience occurring again in the future.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/concepts/

Suppose that an agent has previously had a specific experience, which followed a specific stimulus, and the interaction with their specific disposition. If the same exact conditions were to occur again, the same experience would occur as well.

It is important to note that the actual conception which an agent has, is not equivalent to the correct conception. The correct conception is the logical consequence of the available information.

Given the uncertainty about the future, there is uncertainty about the potential stimulus and potential disposition of an individual. There are a range of potential events which could occur, which means that a range of potential mental events could occur also. For example, a more significant stimulus would lead to a more intense experience.

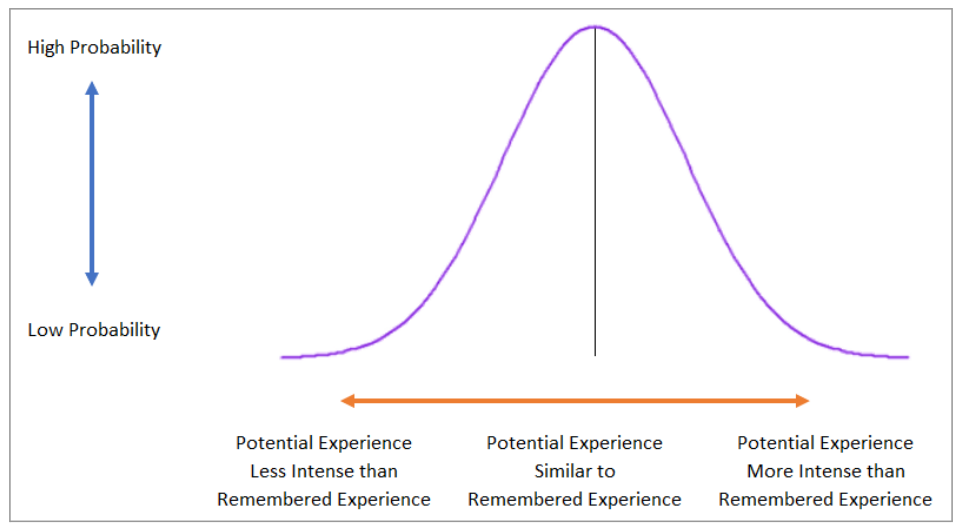

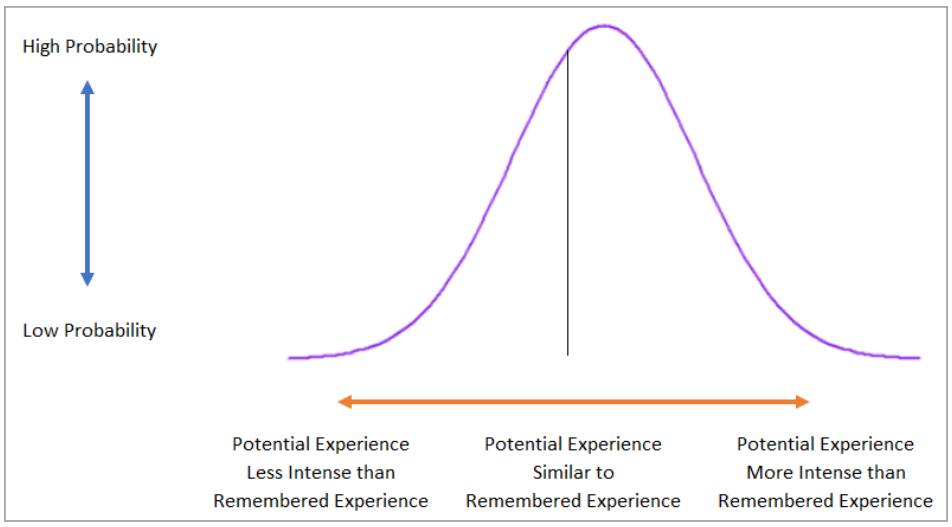

The range of possible experiences can be visualised as a probability distribution. In the diagram below, we are assuming that based on the available information, the potential experience is most likely to be similar to a remembered experience. For example, Angie touched a hot stove last Wednesday, and is considering whether or not to touch it again today.

The agent might have information which suggests that stimulus will be more significant than was the case previously. The next diagram shows that the probability distribution simply moves to the right. Suppose in this case Angie has observed that the stove is even hotter than it was last Wednesday.

The shape of the probability distribution will also be determined by the information available to the agent. More information reduces the standard deviation from the most likely outcome.

Angie has memories of experiencing terrible grief. She can conclude that if the child were to drown, family and friends of the child will be subject to a similar experience. It will not be exactly consistent with her own prior experience, but the range of potential experiences is determined by those memories.

If Angie were to assume that others don’t feel grief in the same way as her, without evidence to support that claim, she would be making an error.

Recap

The agent has information regarding perceptual experience of their current situation, memories of events (including experiences) and the available courses of action. The logical consequence of this information is that each course of action will lead to a different probability distribution of events (including experiences).

There are epistemic modal facts about how good or bad potential experiences would be.

Premise 13: Potential experiences would be better or worse than one another

Premise 13 is inferred from Premises 11 & 12

Given that potential experiences take a similar form to remembered experiences, it follows that some would be better or worse than others.

A potential experience is a conception determined by the available information. The relevant information are the facts about potential disposition of affected individuals, potential stimulus events, and memories of similar situations. The logical consequence of these facts is a probability distribution of potential experience.

Different courses of action will result in different potential experiences. As discussed, modal facts state the valence, intensity and duration of those potential experiences. Comparisons are made on the basis of intensity and duration.

Based on Angie’s memories of past experience, the terrible grief which will potentially occur if she doesn’t save the child would be worse than the discomfort of being cold if she does. These experiences would occur to different people. They would occur in different possible worlds. Despite that, it is a fact that the potential grief is worse than the potential discomfort of cold.

2.4 The Best Course of Action

The final stage in the argument involves the claim that the course of action which will lead to the best set of potential experiences is the best course of action.

Premise 14: Based on the available information, one range of subsequent experiences would be best

Premise 14 is inferred from Premises 5 & 13

The intensity of a remembered experience is perceived by the agent directly through the very act of remembering. Information about this intensity is relative to other experiences. For example, Experience A is perceived to be twice as bad as Experience B, if doubling the duration of Experience B would make them seem equally bad.

If one experience can be better or worse than the aggregate of two experiences, it follows that any range of experiences can be better or worse than another. The determination of which range of experiences is better is a logical consequence of the available information. This information, as shown above, is privately accessed but is not subjective. In theory, any other rational being with the same information would come to the same conclusion about which range of experiences is better.

Based on Angie’s memories of past experience, the range of subsequent mental events which would occur if she attempted to save the child would be better than the range of subsequent mental events that would occur if she didn’t. This is an epistemic modal fact.

Angie might neglect to consider certain subsequent events. Perhaps she doesn’t factor in the many potential positive mental events which could occur if the boy was to be saved. If she doesn’t factor this into her assessment, she may conclude that it would be better if she let the child die. This would be illogical, and factually incorrect.

Recap

The agent has information regarding perceptual experience of their current situation, memories of events (including experiences) and the available courses of action. The logical consequence of this information is that

- Each course of action will lead to a different range of potential experiences.

- Some ranges of potential experiences are better than others.

An objectively true epistemic modal claim can be made that at least one course of action will lead to the best range of potential experiences.

Premise 15: The agent should choose the course of action which is expected to have the best range of subsequent experiences

Premise 15 is inferred from Premise 14

This final premise of the argument follows from the previous one. According to the semantic discussion detailed in Part 1, the claim that one course of action is best is equivalent to the claim that an agent should choose it.

The conclusion of the argument is that a prescriptive proposition can be objectively true. Remember that the term “should” is not used to refer to any authority.

Whether this proposition can be objectively true without reference to any condition, requires some further discussion.

2.5 The Unconditional Best Course of Action

Consider the following propositions which use the term “should”

- Gregor should eat more vegetables

- You should not lie to your friends

- Citizens should obey the law

In each of these cases, the proposition is prescriptive, in that it recommends a course of action. The reason that a particular course of action is recommended is that it will lead to a desired outcome. The desired outcome in each case is implied rather than made explicit. There is a hidden condition for each proposition, which can be revealed as follows.

- Gregor should eat more vegetables, if he wants to be healthy

- To maintain good relationships, you should not lie to your friends

- Citizens should obey the law if they want to avoid punishment

Use of the term should in these examples involves a hidden condition. This condition describes the criteria upon which the recommended action is evaluated. We can say that each of these propositions uses a conditional-should. The challenge for a moral theory is to account for what should be done without reference to conditions. When someone makes the moral claim “You should not do that!” they are (probably) expressing that something should not be done regardless of any specific conditions. We can refer to such use of the term as the unconditional-should.

As detailed in Part 1, Moral Decision Theory refers to the unconditional-should. To understand how we can make such claims, we must first understand the nature of conditions. To explore and explain what is meant by a condition, I will present four different attributes of prescriptive statements.

2.5.1 Stance Dependent or Stance Independent

Use of the conditional-should expresses the stance or desires of the individual who makes the claim. When Gloria says “I should go to bed”, she is actually saying “I should go to bed now, because I am tired”. The hidden condition expresses Gloria’s desire to sleep.

More importantly, it expresses that this desire is her most important consideration. Suppose that Gloria is currently babysitting a small child. Were she to go to bed, she would be abandoning her responsibilities. In this context, the proposition “I should go to bed” expresses that Gloria’s tiredness is more important to her than her babysitting duties. The hidden condition expresses her stance on the relative value of her own sleep and the child’s best interests.

While the conditional-should is based upon desire or stance, the unconditional-should is based upon facts. The unconditional-should is what we might label “stance independent”. A claim using the unconditional-should does not derive its meaning from the desires, beliefs, goals or values of the claimant.

2.5.2 Extrinsic or Intrinsic

A claim which expresses what an agent should do, is an expression of which consequences are considered best. For conditional prescriptive statements, which consequences are best is determined in reference to the condition.

When a doctor says “You should take this medicine” they are making the claim that the action of taking medicine will likely improve your health. The consequences in question are those which relate to health. There is an external standard against which these consequences can be compared. The desirability of consequences is determined by how they compare to the relevant standards.

Reference to an external standard is an extrinsic property. To say that a consequence is desired, according to a condition, is not just a statement about the consequence itself, but about its relationship to a particular standard. A claim using the conditional-should is a claim about the extrinsic properties of the consequences of an agent’s decision. In contrast, a prescriptive claim using the unconditional-should only refers to the intrinsic properties of consequences.

Another way to think about this is to consider why a consequence is defined as good. Taking medicine is good because it leads to good health. Good health is good because it leads to a long life. Long life is good because it involves more positive experiences. The goodness of each consequence (health, long life) is derived from the good experiences which may follow from it.

The same is not true of positive experience itself. A positive experience is good itself, not because it may lead to anything else. An extrinsic property is derivative.

2.5.3 Selective or Absolute

A condition may identify which consequences are to be included and which excluded from a decision. Suppose someone is teaching their child how to play chess, and says “You should move your bishop”. The only set of consequences which are being considered by the conditional-should are those which relate to the game. If moving the bishop is the best strategic option, then the statement is logically correct. However, this conditional-should disregards other consequences. Perhaps telling the child which move to make is counter to teaching the child how to play. Perhaps the child doesn’t enjoy chess and should not be playing.

The conditional-should is selective of which consequences are relevant, and which are excluded from the claim. By contrast, a claim using the unconditional-should is an absolute claim which includes all consequences.

2.5.4 Active or Passive

Placing a condition upon a claim is an action. A person who makes a claim involving a conditional-should can choose which condition they make reference to. Their choice may be instinctive, or even hidden to themselves, but it is a choice which can be made. From this perspective, to place a condition is an active process, by which an individual ascribes value to the potential outcomes.

An unconditional-should is passive in the sense that the individual making the claim is unable to place any condition. We can best understand unconditional-should statements as being “discovered” with reference to the facts, rather than as being “invented” by ascribing value or placing conditions.

2.5.5 Unconditional Prescriptive Epistemic Modal Facts

The table below summarises these four attributes of prescriptive statements.

|

Conditional-Should |

Unconditional-Should |

|

Stance Dependent (Grounded in Belief/Desire/Values) |

Stance Independent (Grounded in Fact) |

|

Extrinsic Property (Derived Good) |

Intrinsic Property (Ultimate Good) |

|

Selective (Some consequences) |

Absolute (All consequences) |

|

Active (Value Ascribing) |

Passive (Fact Uncovering) |

Having worked through the investigation of should statements, we have a better understanding of what is required to make a claim using the unconditional-should. We can now return to Premise 15.

Premise 15: The agent should choose the course of action which is expected to have the best range of subsequent experiences

To understand whether this statement can be interpreted as using the unconditional-should we can look back at the arguments made for premises 1-14.

- Premise 15 is grounded in facts alone. These are the epistemic modal facts about what the agent could choose, what events could occur, which events would be good or bad, and which events would be better or worse. The premise is stance independent.

- The determination of good and bad is intrinsic to the consequent events themselves. We understand that whether a potential experience is good or bad is a property of that experience. It is not in reference to any external standard or condition.

- All subsequent events and experiences are taken into consideration by the proposition. Premise 15 is absolute because there are no conditions or constraints that exclude or diminish certain consequences.

- The proposition does not actively add any conditions, values or evaluative standards. Premise 15 is passive in approach. Instead it requires the agent to uncover the facts of the situation in order to identify the best option.

Following this framework, we can see that Premise 15 uses the unconditional-should.

In conclusion, a statement “Individual X should do Action Y” can be objectively true. Let’s return to the axiom that

An Unconditional Prescriptive Epistemic Modal Fact is

an Action-Guiding Proposition which is a Logical Consequence of All Available Information, without Reference to any Subjective Position

At any decision point, a logical consequence of all available information to the agent, is that a course of action would lead to the best range of subsequent events. The consequence of this, is that there will be an unconditional prescriptive epistemic modal fact regarding which course of action an agent should perform.

2.6 Moral Facts

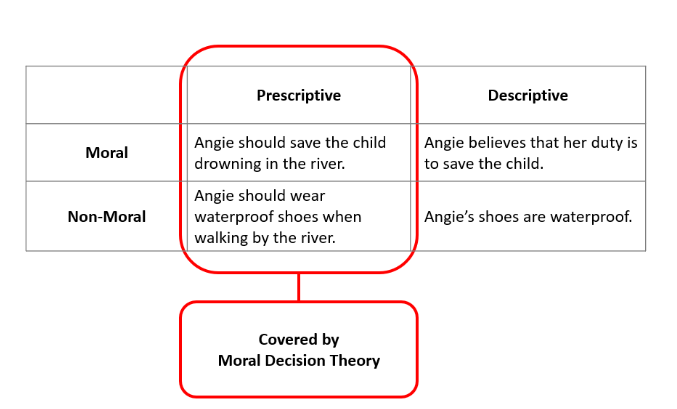

I have now made the case that there are prescriptive facts. But what about Moral Facts? Let’s return to the diagram from Section 1.1.

Generally, people will regard moral facts as being action-guiding and impartial. Such moral facts will therefore use the unconditional-should detailed above. Beyond that, which prescriptive statements are classified as moral facts will be a matter of opinion regarding the moral domain. How someone defines the term “morality” will influence how they categorise moral and non-moral prescriptive facts.

Suppose that a Finance Director is told by their Chief Executive to lie on the company’s annual accounts. Presenting fraudulent information could be damaging to employees, shareholders, and others. However, the Finance Director is offered a large bonus to mis-state the accounts. According to the information available to the Finance Director, it is an objective fact that she should not commit fraud. Some people might see this as a moral issue, while others may feel it is a question of legal duty or professionalism. This distinction is a subjective one. However, if someone believes that the decision of the Finance Director fits within the moral domain, then we can claim that there is a moral fact of the matter.

There will be many competing opinions on which decisions are moral and which are not, which depend on cultural and personal preferences. Where the line is drawn matters for labelling specific prescriptive facts as moral facts. But only the recognition of such a line is needed to agree that some prescriptive facts are moral ones. It can thus be concluded, given that some such statements are objectively and unconditionally true, that there are moral facts.

2.6.1 The Moral “Ought”

A point of contention might be that the term “moral” necessarily involves the implication of normative force or authority. Someone may believe that the claim “Individual X should do Action Y” is only a moral fact if the term “should” carries with it an expression of authority.

Someone taking this position might agree with the argument proposed above for unconditional prescriptive facts. They may agree that a prescriptive statement such as “Angie should save the drowning child” is objectively and unconditionally true. However, this person would believe that the proposition involves some additional property, which carries its normative force.

Moral Decision Theory does not argue for the existence of such a normative force. However, the belief that unconditional prescriptive facts carry such an authority is not contradictory to MDT. Adherence to MDT is compatible with the belief in normative force as long as there is a direct correlation between what is required and the correct decision according to the information available to an agent.

Instead, someone may believe that their moral obligation is to act differently to Moral Decision Theory. This person would recognise that one action would lead to the best range of subsequent events, but that they had a duty to otherwise. This will be further explored in Section 4.4.

Part 2 Coda

Moral Decision Theory

In Advance of Criticism

In Part 2 I have provided an explanation and justification of the central argument for Moral Decision Theory. My goal has been to demonstrate that there is a correct answer to the question “What should we do?” This should be considered as the central claim of MDT which could be reframed as “Certain moral statements can be objectively true”.

If there is any logical fallacy or inconsistency with MDT as a meth-ethical view, then a challenge can be made against the argument above. An opponent of MDT will need to demonstrate that a particular premise is unfounded, or that it does not follow logically from those which have come before. My hope is that by placing the argument in such a format, I will be able to engage effectively with opponents to the theory. It should be clear upon which points we disagree.

The following parts published below are built upon the first principles laid down in Parts 1 & 2. Any arguments which someone might have with these following sections will not be criticism of the central claim of MDT, but a criticism of its application. Opponents may disagree with my views regarding the implications of MDT, but this will not negate the claim that certain moral statements can be objectively true.