Here I present Moral Decision Theory. This is the view that there are objectively true prescriptive claims, some of which may be classified as moral facts. I explain the theory, demonstrate how it can be used, and provide a justification against potential counter-arguments.

Part 1 Prelude

Moral Decision Theory

In a Nutshell

Decision Theory describes which course of action an agent should choose given their specific interests, desires or goals. Under Normative Decision Theory, the optimal decision is the one which best satisfies the agent’s own self-interest. The correct choice is that which a perfectly rational agent would choose given the information available. There can be objectively correct or incorrect choices despite incomplete information.

This standard version of Decision Theory is directed towards the outcomes which are best for the agent themself. The truth of any prescriptive statement, for example, “The agent should take their medicine”, will be conditional upon the interests of the agent. This prescriptive statement is understood to mean “The agent should take their medicine, if they want to be healthy”.

Moral Decision Theory expands the scope of decision making through prescriptive claims which are unconditional. The subjective interests, desires or goals of the agent are not given preference over those of anyone else. The correct decision is determined to be the one which takes account of all outcomes, regardless of whom they might occur to. This impartial perspective results in what may be defined as “moral” decision making.

Just as with traditional decision theory, what an agent should do in a given situation is dependent on the information available to them. However, this dependence upon information does not mean that prescriptive statements are subjective. Instead, objectively true claims can be made about which set of outcomes is best according to the information available. Thus, objectively true claims can be made about which action should be taken.

Moral Decision Theory takes the view that prescriptive statements can be objectively and unconditionally true. However, it does not make any claims about the authority of such statements. Nor does it argue for the existence of objective values. To understand how these seemingly opposing ideas can be reconciled, it is important to provide clarity around terminology.

Part 1

Moral Decision Theory

In No Uncertain Terms

Before getting into the details of the theory, it is very important to be clear on the terms and interpretations being used. Debate about both morality and decision-making can easily get stuck in disagreement over semantics. Misunderstandings can be avoided by being clear from the very beginning.

Language is ambiguous. There are situations in which someone can express what appears to be a fact but is instead an expression of emotion or personal taste. A simple example could be saying “That movie was really great”. The structure of the statement suggests that it is aiming at truth, and of course the claimant could potentially believe that the movie was objectively great. However, it is also possible that the claimant is expressing a subjective preference. In that case, the statement “That movie was really great” is equivalent to “That movie really impressed me”.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/meaning/

Consider a moral statement, such as “The judge should not convict the innocent defendant”. Someone making this claim could either be expressing their subjective position or could be aiming at truth. They could be claiming that the truth of the statement is conditional, perhaps upon the law or upon the judge’s own interests. They might be stating that this is an objectively true moral fact, either because it complies with some principle or duty or because of the consequences which may occur. To properly interpret, discuss and debate the claim, we need to hold a shared understanding of the intended underlying meaning of the statement.

For Moral Decision Theory to be understood and applied, I will define the various interpretations of prescriptive statements. One of these interpretations can express an objectively true proposition. The purpose of Part 1 is to identify this interpretation in preparation for further discussion.

1.1 “Moral”

The first term to discuss is the word “moral”. This means different things to different people and can be used in different ways. For some it includes questions of self-discipline, while for some it refers only to interactions with others. Politeness, sexuality, indecent thoughts, victimless crimes, or a multitude of other criteria could be considered a question of morality for some and not for others.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/morality-definition/

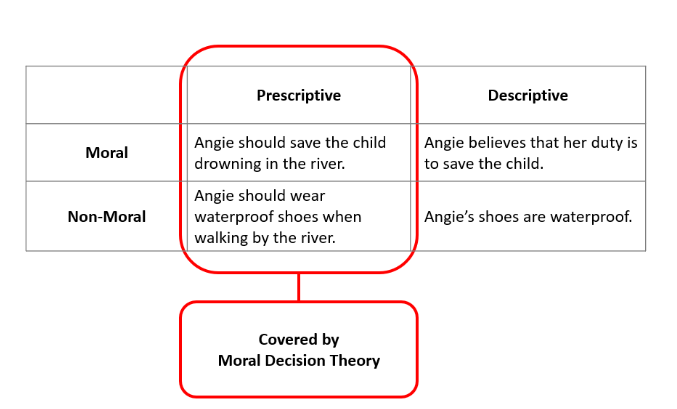

Moral claims can be separated into two categories, descriptive and prescriptive. The first is used to describe the moral beliefs or behaviour of a particular individual or group. This is not relevant for Moral Decision Theory.

The second type is prescriptive. Used in this way, the term is action guiding. In this sense, a moral proposition is one which prescribes which course of action an agent should take. Some prescriptive claims are understood to be moral while others are not.

Suppose that Angie wants to go for a walk by a river. Her friend says “It’s very wet near the riverbank. You should wear waterproof shoes.” This is a prescriptive statement but very few people would consider it to regard morality. Later on, while walking Angie sees that a child is drowning in the river. Angie is a good swimmer, and no one else is around who might save the child. We might conclude that “Angie should save the child”. This is also a prescriptive statement, and one that many people would consider to be a moral one.

Instead of arguing that some moral propositions can be objectively true, I will instead argue that some prescriptive propositions can be objectively true.

Like every other word, and like every other attempt to classify or understand our world, the word “moral” is a creation of social convention. Whether a particular prescriptive proposition is a moral proposition or not is ultimately a subjective preference. I will not put forward any account of how to make this distinction. However, by showing that prescriptive statements may be true, I will be able to show that some prescriptive moral statements are true.

Some moral claims involve a judgement about some prior or hypothetical action, decision, or state of affairs. For example, “The person shouldn’t have lied”, or “Lying is always wrong”. These types of moral claim are also prescriptive in that they identify which actions or behaviours are better or worse than others. They are also action-guiding as they express a judgement as to what someone should do in a similar situation.

1.2 "Should"

For now, we will put the term “moral” to one side, and focus only on prescriptive statements. By focusing on what should or shouldn’t be done, we can avoid any semantic misunderstanding caused by different uses of the term “moral”. However the term “should” is also ambiguous and requires consideration and clarification.

Central to Moral Decision Theory is the claim that some prescriptive statements are true. To present a valid and coherent argument, it is necessary to identify exactly which type of prescriptive claim is being conveyed by the word “should”. Of course, there will be many other ways of using the word “should”. Some of these alternate uses will not be truth-apt, some will be false, and some will simply be irrelevant.

Some opinions will be offered on these other interpretations. However, to prove that one form of a prescriptive statement can be objectively true, it is not necessary to prove that all other forms are not true.

1.2.1 Practical Reason

Moral Decision Theory is concerned with “practical reason”, which refers to decisions about which course of action an agent should take. This is in contrast to “theoretical reason” which refers to what one should believe.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/practical-reason/

There can obviously be an overlap between these two. We can consider the two statements

- Angie should decide to take Action X

- Angie should believe that taking Action X is correct

The first statement uses the term “should” in relation to practical reason while the second is theoretical. Moral Decision Theory is only concerned with the first.

1.2.2 Expressing a Proposition

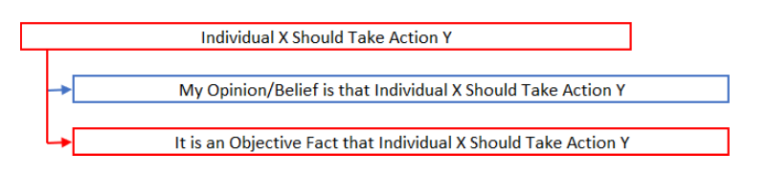

As discussed in the introduction, the same sentence can be interpreted to express either a fact or a feeling.

The same distinction can be made with statements of the form “Individual X should do Action Y”. It is possible that someone who makes this claim is simply expressing their personal preference for Action Y. When a parent tells their child “You should tidy your room” they may not consider that such a statement expresses an objectively true fact. This sentence could be interpreted simply as expressing the command “Tidy your room!”, which cannot be understood as either true or false. It could also be interpreted as an expression of personal preference, equivalent to “I would be happier if your room was tidy”.

Non-cognitivism is a view in meta-ethics which claims that moral sentences do not convey propositions, and therefore, they cannot be either true or false. Under this view, all sentences in the form “Individual X should do Action Y” are understood as expressions of desire or approval. This view claims that every person, in every instance, is incapable of even aiming towards truth when making a prescriptive statement.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/moral-cognitivism/

Moral Decision Theory takes a view that some prescriptive statements express subjective desire or approval, while other prescriptive statements aim towards truth. The semantics are ambiguous, and it is therefore important for the claimant to clarify the purpose of their claim. Statements which may be true or false are known as propositions.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/propositions/

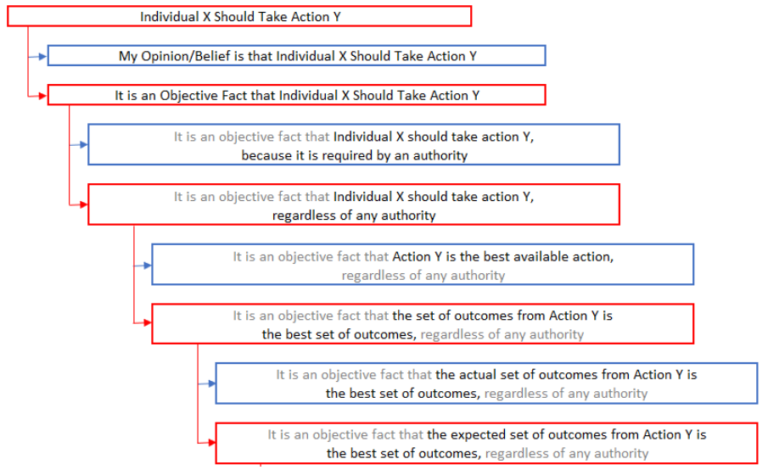

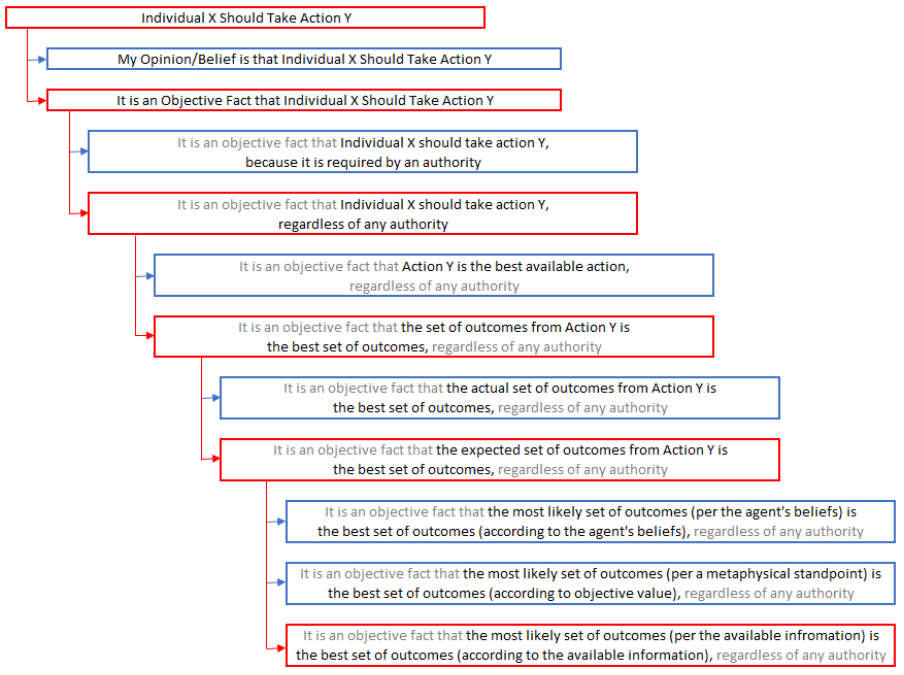

Moral Decision Theory is concerned with prescriptive propositions which aim at truth. We can map this distinction with the diagram below.

1.3 Objective Truth

To put it simply a statement is objectively true when it is true regardless of who is saying it, while a statement is subjective if it refers to the opinions or feelings of the one making the claim.

What is important to understand is that we can make objective statements about subjective positions. For example, when Darius says “I am hungry” he is making a subjective claim. The statement “Darius is hungry” is objectively true. Our opinions, beliefs and desires are subjective, but it is objectively true that we hold them.

To help distinguish between objective and subjective philosophers often use the terms “mind dependent” and “mind independent”. Something is mind-independent if its truth is independent of the existence and thoughts of minds. It would be true even if nobody had thought of it. This is an admittedly confusing perspective to take when considering questions of morality, as we are discussing how decisions affect the feelings and experiences of others. Given that feelings and experiences occur within the minds of other individuals, it seems counterintuitive to say that moral statements can be true independent of minds.

A more helpful term is “stance independence”. Stance refers to beliefs or opinions. A proposition will be true, independent of stance, if the proposition is not contingent on the claimant’s opinions or beliefs.

1.3.1 Unconditional Prescriptive Facts

Consider the statement “Gold is valuable”. This descriptive statement is objectively true. However, we could imagine that in a different context it would not be. The truth of the statement is relative to the demand which society has for gold and its relative scarcity.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/relativism/

A prescriptive proposition, which aims towards truth, can also be expressed with reference to a particular framework, standard or condition. Usually this standard is implied, rather than made explicit. For example, when someone says “Justin should go to church every Sunday” they may actually be expressing the proposition “Because Justin is an Archbishop, he should go to church every Sunday”. This proposition is a true statement, however its truth is conditional upon the context. The concepts upon which its truth is based are all social constructs, being church, Archbishops, and Sundays.

Moral Decision Theory recognises that expression of some prescriptive propositions can be in reference to particular frameworks or standards. The truth of such a proposition is conditional upon a separate statement or assertion. These will be referred to as conditional prescriptive propositions.

Some conditional prescriptive propositions will be true and others will be false. For example, the statement “If Player 1 wants to win, they should move their bishop to C4”. This may be a true statement, but it is conditional upon the statement “Payer 1 wants to win the game”. Such conditional facts are not considered to be sufficient for an objective or universal moral theory, because they involve some subjective desires, beliefs, goals or values.

Under Moral Decision Theory, prescriptive facts make no reference to any subjective position. MDT makes the claim that prescriptive statements can not only be objectively true, but can be true independent of any external framework. Where these claims are true, they are referred to as Unconditional Prescriptive Facts. These are propositions which can be objectively and absolutely true. In summary

An Unconditional Prescriptive Fact is

an Objectively True Action-Guiding Proposition Without Reference to any Subjective Position

Section 2.5 goes into more detail about conditions which may or may not be implied when making a prescriptive claim. These are discussed in relation to decision making, with an explanation of how one can make unconditional prescriptive claims.

1.4 Authority

When it comes to moral statements there is often a presumption that they hold some kind of authority. People talk of actions being morally permitted or morally forbidden, or sometimes of moral duty or moral obligation. This authority, also referred to as “normative force”, is another factor which needs clarification.

Consider the two statements “You should not use bleach to clean a wooden surface” and “You should not feed bleach to a child”. The first is very practical advice while the second is a matter of life and death. We may instinctively feel that these two statements fit into two separate categories. The first is one that we should follow, while the second is one that we should really really follow.

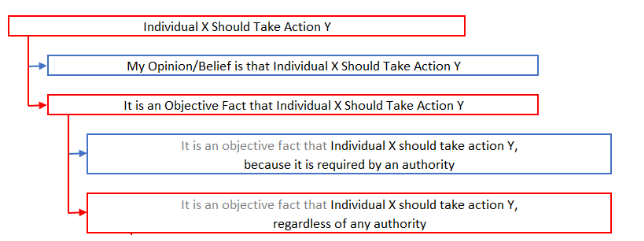

There are four different perspectives through which we can view the authority of prescriptive statements.

- Some true prescriptive statements are true because they have authority

- Some true prescriptive statements have authority because they are true

- Some true prescriptive statements have authority because of some other property

- No prescriptive statements have authority

Moral Decision Theory is specifically concerned with the truth of prescriptive statements, and therefore makes no fundamental claim about whether these statements have any authority or normative force. Despite that, it is important to clarify that MDT is compatible with perspectives 2, 3 and 4.

In Part 2 I will present an argument to show how some prescriptive claims can be objectively true. This argument will not rely on the existence of any natural or supernatural authority. Because the truth of a prescriptive claim is independent of authority, it cannot be the case that authority “comes first”. For that reason MDT is incompatible with the position that an authoritative entity or binding force is what makes certain claims true.

Some readers may find that after reading through the arguments below, they understand that some prescriptive statements can be true. They may then ask themselves how some true statements, such as “You should not feed bleach to a child” seem to hold a normative force while other true statements, such as “You should not use bleach to clean a wooden surface” do not. This question cannot be answered by Moral Decision Theory. Either the reader will be satisfied that their feelings or intuitions about normative force are subjective, or they will have to account for these properties using some other considerations.

To conclude, when prescriptive statements in the form “Individual X should do action Y” are expressed below, they should be interpreted as making no reference whatsoever to duty, obligation, normative force or authority of any kind.

1.4.1 An Authority on Truth

There may be some prescriptive propositions which may be declared by an authoritative figure. For example, Valerie’s doctor says to her “You should take this medicine three times per day”. This statement is not true because it has been made by the doctor. Instead, the truth is dependent on the facts of the situation.

In these cases, an entity is an authority on truth because they have unique access to information. Someone who believes in a supernatural authority may take a similar position, whereby prescriptive statements made by a supernatural being are true, not because the supernatural being has commanded it, but because of the relevant circumstances. The believer may accept the truth of the prescriptive statement because they believe in the infallibility of the supernatural being, but that is not why the proposition is true.

1.5 Forms of Prescription

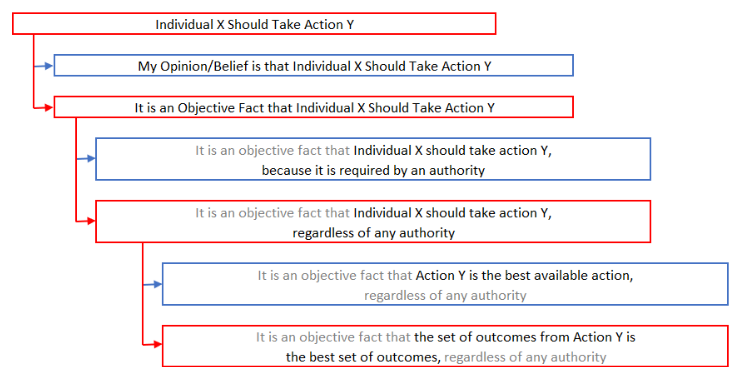

As discussed above, there are many things which may or may not be implied when using the word “should”. Within Moral Decision Theory, the use of “should” expresses an aim towards truth, without regard to any standard or authority. But what does the term actually mean?

The statement “Individual X should do action Y” can be rephrased to exclude the word “should” without changing the underlying meaning. We could instead use the statement “It is correct to perform Action Y” or “Y is the best available action”. These statements express the same underlying proposition.

By rephrasing the statement we avoid the connotation that the agent is obliged or required to perform Action Y. As described above, one may believe that we are obliged or required to perform the correct or best action, but authority is not what makes the action correct or best.

We may now turn our attention to what is meant by the claim that a particular action is “correct” or “best”. We can separate such claims into two broad categories, the “Action-Form” and the “Outcome-Form”. When a proposition expresses that one particular action is correct or best, it will use one of these forms.

1.5.1 Action-Form

Under this interpretation of the term “should”, a prescriptive proposition makes a claim about the value or quality of an action itself. The action, separate from its potential outcomes, is being prescribed.

Consider the following examples

- You should tell the truth

- You should obey the law

- You should say “Thank You” when someone helps you

In statement 1 the underlying proposition can be understood to express that the action of telling the truth is inherently virtuous. The claimant who uses this prescriptive statement could convey exactly the same information by instead using the descriptive statement “It is virtuous to tell the truth”. The underlying meaning of both statements are consistent with one another.

In statement 2 the underlying proposition can be understood to express that obeying the law is the correct thing to do. The claimant who uses this prescriptive proposition could convey exactly the same information by instead using the descriptive statement “It is necessary to obey the law”. The underlying meaning of both statements are consistent with one another.

In statement 3 the underlying proposition can be understood to express that saying “Thank You” is consistent with social norms of politeness. The claimant who uses this prescriptive statement could convey exactly the same information by instead using the descriptive statement “It is polite to say ‘Thank You’”. The underlying meaning of both statements are consistent with one another.

In these three examples, referring to virtue, to rules and to norms, the prescriptive claim makes an evaluation of a specific action or type of action. Similarly, a descriptive statement which describes the value of an action can be used to convey action guiding information. In these statements, which use the action form, the proposition is specifically about the action itself. There is no reference to, or consideration of, the surrounding circumstances or to the potential results of the action.

To understand whether or not a claimant is using the “Action-Form” we can ask them (or imagine asking them) why they have made that claim. If the answer to this question is (or is imagined to be) an evaluation of the action itself, then they are using the “Action-Form”.

Suppose the claimant were to respond that “Lying is wrong” or that “Only evil people lie” then they are using the Action-Form. If however, they respond with “A lie will cause pain” or “Lying will cause others to mistrust me” then they are using the Outcome-Form (see below).

Moral Decision Theory rejects the belief that objectively true prescriptive statements can be made using the “Action-Form”.

1.5.2 Outcome-Form

The alternative use of the term “should” refers not to the action directly but the expected or actual outcomes which follow the action. Consider the following examples

- You should take your medication

- You should move your bishop to C4

- You should help the old lady to cross the road

In statement 1 the underlying proposition can be understood to express that taking the medication will lead to positive health outcomes. The claimant who uses this prescriptive statement could convey exactly the same information by instead using the descriptive statement “Taking your medication will be good for you”. The underlying meaning of both statements are consistent with one another.

In statement 2 the underlying proposition can be understood to express that moving the bishop will increase the likelihood of victory. The claimant who uses this prescriptive statement could convey exactly the same information by instead using the descriptive statement “Moving the bishop to C4 will lead to a victory”. The underlying meaning of both statements are consistent with one another.

In statement 3 the underlying proposition can be understood to express that helping the old lady will enable her to reach her destination safely. The claimant who uses this prescriptive statement could convey exactly the same information by instead using the descriptive statement “Helping the old lady will reduce the risk of an accident”. The underlying meaning of both statements are consistent with one another.

These three examples show that a prescriptive statement in the form “Individual X should do Action Y” can also be expressed using the descriptive statement in the form “The outcomes from Action Y would be best”. This is the underlying meaning of prescriptive statements which are made within Moral Decision Theory. This does not mean that every use of the term “should” refers to outcomes rather than to the action directly. What it does mean, is that for a prescriptive proposition to be true, it must use the “Outcome-Form”.

The table below details the prescriptive proposition which is expressed under Moral Decision Theory.

1.6 Forms of Modality

“Should” is a modal verb. Within grammar there are many different ways which a modal verb can be used. An expression made under Moral Decision Theory refers to the outcomes of an action, or more accurately from a decision. These outcomes are possible events which may or may not occur.

The potential events can be discussed and deliberated upon using modal terms. For example

- If the agent chooses Action A, then Event 1 could occur.

- If the agent chooses Action B, they would be affected by Event 2

These statements could be used to express either of two form of modality; metaphysical or epistemic.

1.6.1 Metaphysical Modality

Propositions which refer to what is actually possible or what could have been possible under different circumstances express metaphysical modality. Consider the following statement

“It is possible that the train could be delayed due to mechanical issues.”

This claim aims to convey information about the real world, and the interaction of events within it. The truth or falsity of the proposition is contingent on actual facts of the real state of affairs.

Prescriptive statements made within Moral Decision Theory do not express this form of modality. This is important to remember, as it means that the truth of such prescriptive statements are not contingent upon any actual facts – those which are about the real world.

1.6.2 Epistemic Modality

Propositions which refer to what is possible or what could be possible given a certain body of information express epistemic modality. Consider the following statement

“It is possible that the train could be running late.”

This claim conveys the conclusion which can be drawn from the information available to the claimant. Even if the train, in reality, is on time, if the claimant is unaware of this fact, the statement will hold true. The truth or falsity of the proposition is not contingent on actual facts, but upon the information available.

Prescriptive statements made within Moral Decision Theory express this form of modality. This is important to remember, as it means that the truth of such prescriptive statements are contingent upon the information available. To understand Moral Decision Theory, it is essential that the reader keeps the following in mind

An Epistemic Modal Claim is Objectively True if it is

a Logical Consequence of All Available Information

Suppose that Erin and Frank are on a train, while their friends Glenda and Henry are awaiting her arrival at the station. The train is scheduled to arrive at 7pm, but it has been significantly delayed. Henry, unaware of the delay, says to Glenda, “The train could be here at 7pm”. Meanwhile, Erin says to Frank “It is impossible for this train to arrive at 7pm”. While these two statements are contradictory, both are objectively true when interpreted as epistemic modal claims.

If this seems counterintuitive, it is because we are aware of information which is not available to Henry. The underlying proposition can be reframed as “According to the information available to Henry, the train could arrive at 7pm”. By clarifying exactly what is being expressed, we can better understand that the claim is an objective fact.

1.6.3 Possible Worlds

Propositions which refer to possibility instead of actuality can be understood by considering possible worlds. The use of this concept will help to differentiate between the two forms of modality.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/possible-worlds/

Continuing the story from above, Erin and Frank’s train finally arrives at 7:30pm. Frank says to his friends, “We could have arrived on time if there wasn’t a signal failure”. This claim describes a possible world which would have occurred if the actual state of affairs had been different. Frank is referring to metaphysical modality.

Glenda responds saying “The signal failure might not have been the reason for the delay”. Her claim refers to epistemics modality. Glenda is saying that, according to the information available to the group, there are possible worlds in which some other event caused the train to be delayed. The possible worlds are not taken to actually “exist”. It simply represents a state of affairs that is compatible with what is currently known or believed, even if it may not correspond to the actual world.

The table below details the prescriptive proposition which is expressed under Moral Decision Theory.

1.7 Best

As explained above, a prescriptive statement in the form “Individual X should do Action Y” can also be expressed using a statement in the form “The outcomes from Action Y would be best”. But what is meant by “Best”?

1.7.1 Value

As discussed above, central to Moral Decision Theory is a focus on the outcomes of a decision. This approach is reminiscent of an approach to morality known as consequentialism.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/consequentialism/

A broad definition of Consequentialism is that determination of the correct action involves consideration of consequences. Moral Decision Theory would fall under this wide definition. However, the standard view of Consequentialism makes a further claim that the correct outcomes have “value”.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/value-intrinsic-extrinsic/

There are various perspectives on what has value and whether value can be objective. Regardless of these distinctions, it is important to understand that value is supervenient.

Suppose that a particular consequent state of affairs is claimed to be valuable, for example, those arising when someone helps an older lady to cross the road. We can identify many of the non-evaluative elements of this state of affairs

- The risk of accident is reduced

- The older lady feels safe and grateful

- The kind stranger feels pride

None of these elements is understood to be “value”. Instead, value is something which supervenes upon these features of the situation. It is claimed that some additional property of the state of affairs is objectively valuable.

Moral Decision Theory makes no reference to value, whether objective or subjective.

1.7.2 Valence

Where Moral Decision Theory theory differs from those theories which refer to value is that reference is only made to the non-evaluative features of the situation. Instead of the terms “good” and “bad” being used to describe moral properties, they are used to describe the intrinsic properties of subjective experience.

Certain emotions, moods and feelings are good while others are bad. The term valence is used to denote whether an experience is intrinsically positive or negative.

Considering subjective experience as a mental event, or a consequence of a decision, means that we can describe good and bad consequences not in terms of value but in terms of valence. The claim “The outcomes from Action Y would be best” refers to the best range of mental events. The “good” qualities of these mental events are intrinsic properties of the experience, rather than any value which supervenes upon them.

Of course, positive emotions are going to be valued by a subject and perhaps by others who care about them. However, this value is unconnected to the objective facts which determine the correct decision.

For the final time, the table below details the prescriptive proposition which is expressed under Moral Decision Theory.

1.8 Objective Truth Revisited

When a claim is made under Moral Decision Theory “Individual X should perform Action Y” the underlying proposition should be interpreted as “It is an objective fact that the most likely set of outcomes of Action Y will be best, per the information available to Individual X” It is a mouthful to explicitly include these clarifications whenever making a statement, so the form “Individual X should perform Action Y” will be used instead.

1.8.1 Epistemic Modal Facts

We now revisit the concept of objective truth (Section 1.3) to understand how it is applied to prescriptive propositions made under MDT.

To claim that the truth of a proposition is stance independent means that its truth is dependent on the facts. In everyday usage, a fact is a true proposition which refers to the actual way that things are. An example of an actual fact would be that “the moon is smaller than the earth”.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/facts/

In addition to actual facts, we can state facts about the information available to an individual. In the scenario described in section 1.5, it is an actual fact that “At 7pm, Glenda observes that the train has not arrived at the destination”. A logical consequence of the information available to Glenda is that “The train could arrive at 7:05pm”. This claim doesn’t refer to reality, because in reality, the train is so far away that arriving at 7:05pm is a physical impossibility. Instead, we might refer to the claim that “The train could arrive at 7:05pm” as an Epistemic Modal Fact. It is objectively true, because it is a logical consequence of the information available.

An Epistemic Modal Fact is a Proposition which is

a Logical Consequence of All Available Information

1.8.2 Unconditional Prescriptive Epistemic Modal Facts

We can now combine the definitions detailed above. In 1.3.1 I explained that

An Unconditional Prescriptive Fact is

an Objectively True Action-Guiding Proposition which makes No Reference to any Subjective Position

We combine this with the definition in 1.7.1 above, to provide a definition for Unconditional Prescriptive Epistemic Modal Facts.

An Unconditional Prescriptive Epistemic Modal Fact is

an Action-Guiding Proposition which is

a Logical Consequence of All Available Information

and which makes No Reference to any Subjective Position

In Part 2 I will explain how it is that we can express Unconditional Prescriptive Epistemic Modal Facts. These facts prescribe the best course of action according to the information available to an agent. This means that for every decision, there is a best option available, regardless of any conditions.

We now have a common understanding of what is being expressed by the claim “Individual X Should Perform Action Y”. Before moving on, there is one final concept which relates to epistemic modality and is central to decision making which must be defined – probability.

1.9 Probability

Decisions are future oriented. The decision of which course of action to choose requires an assessment of how the action may affect future events. The probability of an event occurring is therefore central to the decision, which requires an understanding of what exactly probability is.

For our purpose, and broadly speaking, there are three ways to interpret or express probability.

1.9.1 Physical Probability

Some may believe that probability is something which actually exists, in the world, independent of any beliefs or perspectives. This suggests that events or outcomes have a certain likelihood or chance of occurring, rooted in the intrinsic structure and dynamics of the universe. This somewhat corresponds with the concept of metaphysical modality which was discussed above.

This interpretation of probability is used in certain scientific statements, such as “After one half life, there is a 50% probability that a particular nucleus will have decayed”. Given that Moral Decision Theory is concerned with epistemic modal facts, it has no reference to physical probability.

1.9.2 Information-Relative Probability

This interpretation is generally known as “Evidential Probability”. To be consistent with terminology used elsewhere, I will label it “Information-Relative Probability”.

Probability can be understood as an expression of incomplete information. Suppose a deck of cards is shuffled and placed on a table in front of Errol. Given the information available to him, there are 52 different cards which could be at the top of the deck.

Suppose we could conceive of every epistemically possible world in which the top card is the Ace of Spades. For each one of those possible worlds, there is another possible world which is identical in every single way, except that the top card is the 2 of Spades. We can continue through the deck to divide the total number of worlds which are possible, according to Errol’s information, into 52 sets of equal quantity. The following statement is an objectively true epistemic modal claim

“In 1/52 possible worlds, the top card is the Ace of Spades”

Another way of expressing this same information is to say that there is a 1/52 probability that the top card is the Ace of Spades.

Now suppose that someone else, Agrippa, sits down at the table. She is allowed to take the bottom 47 cards from the deck and look at each of them. She now has information which makes it impossible for 47 cards to be at the top of the deck. There are many worlds which are possible according to the information available to Errol, but which are impossible according to the information available to Agrippa.

We can divide the total number of worlds which are possible, according to Agrippa’s information, into 5 sets of equal quantity. Supposing that Agrippa doesn’t see the Ace of Spades, the following statement is an objectively true epistemic modal claim

“In 1/5 possible worlds, the top card is the Ace of Spades”

Another way of expressing this same information is to say that there is a 1/5 probability that the top card is the Ace of Spades.

To summarise, the following axioms are held to be true by Moral Decision Theory

- According to a body of information, there is a total population of possible worlds

- According to a body of information, a set of possible worlds can be identified by a shared property or the occurrence of a similar event

- The quantity of the identified set as a proportion of the total population, can be referred to as the information-relative probability

Given that the probability is dependent on the body of information, it is stance independent.

1.9.3 Credence

A final interpretation of probability may be referred to as subjective probability or as an interpretation of belief. In this case, the statement “It will probably rain tomorrow” may express the relative certainty of the claimant’s belief. The propositions which are determined to be true by Moral Decision Theory make no reference to credence. However, it is important to understand the distinction between epistemic modal claims.

Suppose that you were to toss a fair coin ten times. Will you toss heads at least four times in row, at any point during the ten tosses?

Depending on your intuition, influenced perhaps by previous experience with coins or other 50/50 events, you might estimate the likelihood. One person might be 90% sure, while another is only 10% sure. Given that credence expresses subjective opinion, neither is considered to be wrong.

To further complicate things (or differentiate things), we can consider a credence which refers to information-relative probability. Someone who has studied probability theory could calculate that there was a 25% chance of getting heads at least four times in a row. But, they may not be 100% certain that they have performed the calculation correctly. In such a case, they are 95% sure (credence) that there is a 25% chance (information-relative probability).

Part 1 Coda

Moral Decision Theory

In Progress

I have written about Moral Decision Theory in 5 parts, with further parts currently being worked on.

Part 1 – MDT In No Uncertain Terms

This introductory section covers terminology, and sets out the objective – to demonstrate how prescriptive propositions can be true, when they express a position of epistemic modality.

Part 2 – MDT In Principle

This part works through an argument to show how prescriptive propositions can be objectively and unconditionally true. This is the central meta-ethical claim of Moral Decision Theory.

Part 3 – MDT In Practice

This part moves on to Normative Ethics. I explain how agents can make decisions under the theory, investigating the process of deliberation and its practical implementation.

Part 4 – MDT In Defence

In this part I consider some potential arguments which may be raised against Moral Decision Theory. For each of these, I provide a response, or further clarification which may resolve any misunderstandings.

Part 5 – MDT In the Extreme

This part reviews Moral Decision Theory under various hypothetical situations, to test its universality. This section will give readers a further understanding of how MDT can be applied in a variety of situations.

Part 6 – MDT In Retrospect (IN PROGRESS)

This part will explain how we make moral judgments. Moral Decision Theory is ultimately forward looking, but can be applied to actual decisions already made by considering the information available to the agent at the time. This part will include discussion of praise, blame and moral luck.

Part 7 – MDT In General (IN PROGRESS)

I will look at how and why we make decisions to create rules. This will cover the logic of implementing rules, systems and norms to bring about the best range of subsequent experiences. This applies to decisions made by individuals and groups.

Part 8 – MDT In Response (IN PROGRESS)

Following on from the previous section, this part will look at decisions an agent makes to follow or break a rule. It will then look at decisions we make in response to those who break rules, looking at punishment under MDT.

Part 9 – MDT In Virtue (IN PROGRESS)

This section will be looking at values and virtues in the context of Moral Decision Theory. Ultimately, values are tools or heuristics which can help us to follow MDT without the need for extensive deliberation. These are subjective, but can enable us to identify the objectively best course of action under certain contexts.

Part 10 – MDT In Reality (IN PROGRESS)

Here I will delve into applied ethics. I will look at various questions of moral decision making and show how MDT can be applied. This will include decisions involving death (murder, euthanasia, abortion, conflict, eating animals), theft and other areas of human interaction.